America’s royal family of jazz includes a number of Kings, at least one Count, and the singular Duke Ellington. Nobody could beat the Duke for sheer style and sophistication. His fan club spans several generations and several continents. His compositions embody the entire spectrum of jazz. On this radio broadcast, we’re celebrating the Ellington musical legacy with an artist who graced his bandstand for many years—a star of the original Tonight Show band, one of America’s great jazz masters and jazz educators, Clark Terry. In 1956, Duke Ellington introduced Clark Terry by describing him as “a great trumpet player, a man who in jazz circles is considered ‘beyond category.’”

Young Duke Ellington photo courtesy audioz.info

Born in 1899, Edward Kennedy Ellington grew up in Washington, DC. From his father who was a butler, he inherited a taste for the finer things in life—gourmet foods, fine wines, elegant manners. The story goes that Ellington’s self-confidence and flashy clothes as a young man won him the nickname “Duke.” Early on, he felt the pull of the bright lights of the big city up north. In 1922, fronting his first band, the Washingtonians, Duke made his move to New York.

Recalling that time in his life, he said, “Harlem in our minds did, indeed, have the world’s most glamorous atmosphere. We had to go there.” In the 20s Harlem was an attitude, a mood that infected Duke’s music. Fats Waller, Willie “The Lion” Smith and James P. Johnson were making waves, making a new kind of music in Harlem night clubs. Black writers and artists forged a movement that came to be known as the “Harlem Renaissance.” Inspired by it all, Ellington went on to write his Harlem Suite, “Echoes of Harlem” and his pop tune that kicks off this radio show, “Drop Me Off in Harlem.”

The Washingtonians photo courtesy redhotjazz

Jim Cullum says, “Duke Ellington wasn’t one of those geniuses who burned brightly for only a short time. He had great staying power. Many of the tunes he wrote became great standards for jazz jam sessions over the years, and that’s just what we’re going to dish up for you tonight.“ Jim Cullum and his Band recall this informal “jam” atmosphere by offering an historical recording of Ellington’s “Black and Tan Fantasy” recorded by the Louis Armstrong All-Stars, a counterpoint to the more commonly heard formal full band arrangements of the Ellington Orchestra on this number. On our broadcast, the historical recording of “Black and Tan” transitions into a live performance on stage at The Landing by The Jim Cullum Jazz Band.

Young Clark Terry photo courtesy of the artist

Our special guest trumpeter and master of the flugelhorn Clark Terry recalls the musical education he received as a boy via radio, a relatively new medium at the time:

“During the time when I was a kid we all had crystal radio sets; that was about the best you could come by in those days. They were very limited as far as listening quality, so we would put them in huge mixing bowls in order to make them sound louder. We’d figure out ways and means of imitating the sounds we heard from various bands, which were broadcasting from different parts of the world.

We didn’t have instruments in many instances, so we had to make some makeshift instruments. The bass player took an old vacuum cleaner hose and wrapped it around his neck and stuck the end of it into a beer mug. I took an old garden hose and wrapped it up and in the three areas where the valves appear I wrapped them up with wire so that they looked like valves, stuck an old kerosene funnel in the end to look like a bell, and a lead pipe for a mouthpiece. Man, I could make a lot of noise on it, couldn’t make any music though. I made so much noise on that thing that the neighbors got sick of it, and they chipped in and bought me a trumpet.”

Clark worked with bands led by Charlie Barnet, Lionel Hampton and Count Basie, but he says it wasn’t until he joined Ellington that he came into his own musically. “[Duke] stuck me in the section with guys like Cat Anderson, Harold Baker, Willie Cook, Joe Wilson, people of that sort, really big-name guys. I learned to govern myself accordingly, I learned a lot from these guys.”

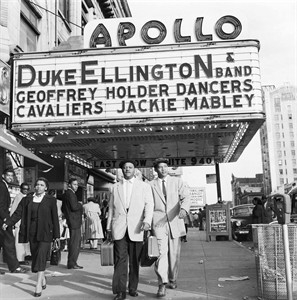

1955 trumpeter Clark Terry, second from right, as he walks with his son Rudolph, right, under the Apollo Theater marquee after Terry’s first stage show with Duke Ellington‘s band in the Harlem neighborhood of New York. Photo from Harlem World

Duke Ellington and his Orchestra travelled many thousands of miles around the globe as ambassadors of good will for the State Department, and on their own. Through changes in fashion, musical trends and pressures to commercialize his sound, Ellington endured, steadfastly remaining true to his ideal. For some fifty years, through good times and bad, whether they were making money or not, Duke kept his outstanding orchestra together, and on the road.

Duke Ellington was a man who did things in his own way. He loved to pour on the charm, laugh and enjoy life. He was notoriously superstitious, refusing to wear certain colors, filling his pockets with medallions and good luck pieces. The men in Ellington’s band thought he was the greatest. Some of them seemed to sign on for life when they joined his orchestra. Both saxophonist Toby Hardwick and drummer Sonny Greer were in Ellington’s very first band in the 1920s and stayed on for decades. The great alto saxophonist Johnny Hodges was with Ellington for 48 years. At age 18 Billy Strayhorn joined Ellington as his musical collaborator and arranger. Strayhorn stayed with Duke for the rest of his life. Clarinetist Barney Bigard said, “Everyone in that band knew they were working for a genius.”

Though he wrote his first composition “Soda Fountain Rag” as a teenager, Duke Ellington was almost 30 before he began creating a significant body of work. He was 40 years old before he came into his own artistically, and then he took off—writing scores for Hollywood, Broadway and the concert stage, tapping into classical themes. Scoring for the highly individual sound colorations of each player in his band, he managed to represent the entire spectrum of jazz: from Stride and New Orleans jazz to Swing and Bop, eventually incorporating Latin rhythms into the Orchestra’s repertoire.

In 1946 the Duke Ellington Orchestra swept the Down Beat magazine poll. By the early 50s the band fell into a period of decline as musical tastes in the country changed, and some of Duke’s ‘old hands’ left the Orchestra. But in 1956 at the Newport Jazz Festival, the Duke Ellington Orchestra rocketed back into the spotlight with a fabulous rendition of Ellington’s “Diminuendo and Crescendo in Blue.” It was after midnight. The great stars headlining the Newport Festival had already left by the time Duke and his Orchestra took the stage. Halfway through the piece, the crowd began to shout and go crazy. The Duke was back.

Clark Terry with The Jim Cullum Jazz Band. Photo courtesy Riverwalk Jazz.

Playlist Notes

Tunes on this broadcast featuring Clark Terry sitting in with The Jim Cullum Jazz Band include: “Ring Dem Bells,” an Ellington original composed for the 1930 Amos 'n Andy film Check and Double-Check, remains a jazz staple to this day.

“Take The A Train” from 1940 was the first tune Billy Strayhorn composed for the Orchestra and Duke adopted it as his band theme. Over the decades, Ellington/Strayhorn classics like “Mood Indigo,” “It Don't Mean a Thing (if It Ain't Got That Swing),” “Come Sunday” and “Sophisticated Lady” are today collectively regarded as cornerstones of jazz repertoire.

Duke Ellington celebrated his 70th birthday in 1969 back in his hometown Washington DC, but this time as a guest at the White House. He was honored by President Nixon in the East Room, the same room where his father had occasionally worked as a butler around the turn of the century. Nixon presented Duke with the Presidential Medal of Freedom, after which Duke reflected:

Duke Ellington receiving the Presidential Medal of Freedom,1969. Photo courtesy Wikimedia free use

“We would like very much to mention the four major freedoms that my friend…Billy Strayhorn lived by: freedom from hate, unconditionally; freedom from self-pity; freedom from the fear of possibly doing something that may help someone else more than it would him; and freedom from the kind of pride that could make a man feel that he is better than his brother.”

Text based on Riverwalk Jazz script by Margaret Moos Pick ©1991