.jpg)

Austin High Gang. Photo in public domain.

Nobody realized it at the time, but in the early 1920s America was about to become the entertainment capital of the world. The twin birth of radio broadcasting and the recording industry launched new industries that would topple the age-old supremacy of European culture in the new world. The driving force behind this revolution was a new music with a rollicking, two-beat rhythm, tailor-made for a party-going generation. The first band to make a hit record with this new sound combined a zany vaudeville act with syncopated rhythms. The Original Dixieland Jazz Band took old New Orleans rags and "camped them up" on their first recording session. Young white kids hearing these throbbing rhythms for the first time went a little crazy. It was a phenomenon much like the rock 'n roll revolution of the 1950s. Jazz provided an outlet on the dance floor, and its rowdy beat upset parents who called it the ‘devil's music.’ Very few people saw any artistic merit in jazz at the time.

Here, New Orleans trumpet player Nicholas Payton and The Jim Cullum Jazz Band perform “Tiger Rag,” in an authentic style—it’s a hot ODJB tune that taught the Roaring Twenties generation to “cut loose.”

The New Orleans Rhythm Kings were one of the first white bands to succeed in jazz. Musicians, including cornetist Bix Biederbecke and saxophonist Bud Freeman, were deeply influenced by the NORK. The band had a strong front line with Paul Mares on cornet, George Brunies on trombone, and the wildly brilliant Leon Rappolo on clarinet. Rappolo’s personality was just as eccentric as his playing was brilliant. Like Bix, he was a victim of Jazz Age excess. It's said that on windy nights Rappolo would lean up against a telephone pole, and listen to the wind whistling through the wires overhead. In a trance, he'd play his clarinet to harmonize with the singing of the telephone lines.

New Orleans Rhythm Kings. Photo courtesy Wikimedia.

On this week’s show, we hear the New Orleans Rhythm Kings original 1923 Gennett recording, featuring Rappolo's famous clarinet solo on "Tin Roof Blues," followed by a live crossfade to The Jim Cullum Jazz Band's rendition.

One afternoon in 1922, a gang of kids found themselves hanging out at their favorite ice cream parlor—a neighborhood place called the Spoon and Straw on Chicago's middleclass west side. The Spoon and Straw was their daily haunt after classes at Austin High across the street. Ranging in age from 14 to 17, there were the McPartland brothers Jimmy and Tommy, and their buddies Bud Freeman, Jim Lannigan and Frank Teschemacher. The big draw at the Spoon and Straw was a wind-up Victrola and a stack of records. Most were bland, pop tunes by society orchestras, the kind of thing their parents would like.

On this particular afternoon, they discovered a new batch of 78s by a band no one had heard of —The New Orleans Rhythm Kings. The kids were blown away by hot tunes like, "Tin Roof Blues," "Tiger Rag" and "Farewell Blues." They spent five hours at the Spoon and Straw, playing the NORK 78s over and over. On the spot, they formed their own band and settled on the name, ‘The Blue Friars,’ after The Friars Inn on the Chicago Loop where their heroes The New Orleans Rhythm Kings played. Too young to get into the club, they would stand on the sidewalk, hoping the door would open and give them a few seconds of their heroes’ music loud and clear.

Frank Teschemacher. Photo in public domain.

Of course, these jazz-crazed high school kids couldn’t read or write music themselves, and they begged and borrowed to get instruments for their band. Every spare moment was spent learning jazz tunes off records. “Farewell Blues” was the first one they picked up. Jimmy McPartland taught himself to play the cornet, his brother Dick the banjo. Bud Freeman got a C-Melody saxophone, a popular instrument in the 20s. Frank Teschemacher latched onto a clarinet, and Jim Lannigan found himself a sousaphone. They picked up drummer Dave Tough from nearby Oak Park High and a piano player by the name of Dave North. Even before they had enough tunes to fill a set list, the Blue Friars were playing for fraternity parties and tea dances.

On our show this week, British-born pianist Marian McPartland (host of NPR's long-running Piano Jazz) talks about the Austin High Gang with host David Holt. Marian met and married Jimmy McPartland in Britain in 1945 toward the end of WWII. By then, Jimmy was established as one of the foremost jazz cornetists. But in the early days of the Austin High Gang, Marian recalls the young players’ attitude was "if you read music, you’re not a jazz player." McPartland notes, "They evidently didn't quarrel, everybody was so into the music they just learned their parts and played, and that's why they were so good."

Austin High saxophonist Bud Freeman recalled going to the Lincoln Gardens on the South Side of Chicago in 1923 with the McPartland boys to hear Louis Armstrong play with King Oliver for the first time. It was a "blacks-only" club, but somehow they made it past the bouncer and up to the bandstand where they stood in awe. Freeman later said, "I knew at once I was hearing a master. Louis was the great American voice—a genius—and his guide and idol was King Oliver, and nothing would ever be the same again.”

Jimmy and Marian McPartland. Photo courtesy Marian McPartland.

On this radio show, The Jim Cullum Jazz Band plays the King Oliver tune "I Ain't Gonna Tell Nobody" in the classic New Orleans improvised-ensemble style.

Cornetist Bix Biederbecke had a huge influence on the young Chicagoans. Though not much older than the Austin High Gang, Bix was far more sophisticated musically. Bud Freeman recalled the night Bix promised to take him and Frank Teschemacher to hear “the greatest singer in the world.” On Bix's night off from playing with the Wolverines, the three of them grabbed a cab to the Paradise Gardens on 33rd Street, where clarinetist Jimmie Noone had a small ensemble. Noone's quartet opened its first set after midnight with the tune "I'll See You In My Dreams." Bessie Smith strolled among the club’s tables singing chorus after chorus of this tune, each more stunning than the one before. The story goes that Bix showered Bessie Smith with all the money he had in his pockets. Bud Freeman said, "She had the most fantastic voice I've ever heard. From then on, I bought every Bessie Smith record I could find."

On this edition of our radio show, New Orleans' Topsy Chapman celebrates Bessie Smith singing her "Down-Hearted Blues."

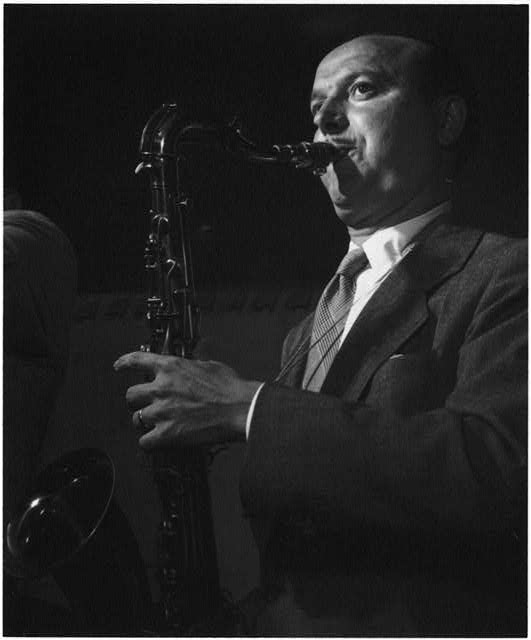

Bud Freeman. Photo © William P. Gottlieb, courtesy Library of Congress.

Of all the members of the Austin High Gang, saxophonist Bud Freeman was the slowest learner, though he went on to become a widely influential jazzman, a virtuoso and among the first to introduce saxophone into small jazz bands.

Here, saxophonist Ken Peplowski joins The Jim Cullum Jazz Band to pay tribute to Bud Freeman with a sizzling performance of his best-known tune from 1933, "The Eel."

More than anyone else on the Chicago jazz scene, Jimmy McPartland admired the lyrical tonal quality of Bix Beiderbecke's cornet playing. This "Bix-ish" style somehow managed to be both hot and melancholy at the same time. By 1923 Bix was the star soloist of Wolverines. When he left the band in 1925, Bix called Jimmy McPartland to take his place.

In conversation with host David Holt, Marian McPartland reminisces about the special relationship between Bix and Jimmy: "Jimmy just loved it when Bix said to him, 'I like you, kid. You play like me but you don't copy me.'" Recalling that Bix bought a new cornet for Jimmy, Marian says, "Jimmy never had any money. None of those guys ever had any money."

Jimmy McPartland soon found places on the Wolverines band for most of his pals, but it wasn’t long before the Wolverines broke up. In 1927 Eddie Condon recorded the Austin High Gang as the Mackenzie-Condon Chicagoans. This session launched the young musicians from Chicago into a new level of professionalism. With the notoriety of these recordings, they all developed successful careers in New York, playing and recording with musicians like Jack Teagarden, Pee Wee Russell, Benny Goodman and Tommy Dorsey. Out of the original Austin High Gang, Jimmy McPartland and Bud Freeman sustained the longest and most acclaimed careers in jazz.

The Austin High Gang weren't the only white kids in Chicago aspiring to be taken seriously as jazz musicians. When he was a boy, Benny Goodman got his first clarinet in a band at the Hull Settlement House. Eddie Condon, a fast-talking young guitarist, had been playing gigs there since he was 17. Cornetist Muggsy Spanier, drummer George Wettling, clarinetist Mezz Mezzrow and trumpeter Wild Bill Davison were all "young lions" on the Chicago Jazz scene.

Chicago was a hub for a thriving black jazz scene in the 1920s, too. Jelly Roll Morton, Louis Armstrong, Little Brother Montgomery, Jimmy Yancey and Pine Top Smith are just a handful of the black jazz and blues musicians to make Chicago home base.

Photo credit for Home Page: Austin High Gang. Photo in public domain.

Text based on Riverwalk Jazz script by Margaret Moos Pick ©1997