Riverwalk Jazz takes a peek behind the famous doors of America’s brightest jazz clubs from New Orleans’ Mahogany Hall at the turn of the twentieth century to The Landing in San Antonio today.

52nd Street, New York City, 1948. Photo courtesy of Library of Congress.

Great moments in jazz can happen almost anywhere—in smoky basements so dimly lit patrons can barely see who’s sitting across the table, or in glittering show rooms packed with celebrities. On this broadcast, we stroll through history to visit the jazz world’s favorite nightclubs and hot spots, remembering remarkable jazz scenes of the twentieth century, from its glory days in the 1920s on the South Side of Chicago to Manhattan’s West 52nd St. in the 1940s. We’ll drop in on the Sunset Café, the Cotton Club and the Famous Door. Then we’ll take a trip out west to the Reno Club in Kansas City and visit Earthquake McGoon’s in San Francisco before winding up at the Landing in San Antonio, Texas.

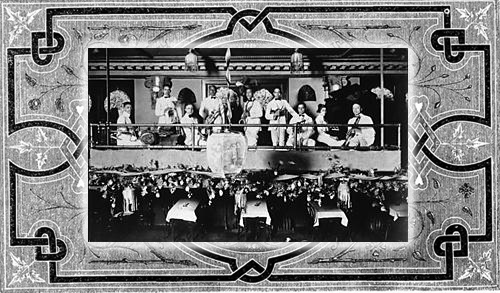

Basin Street postcard 1907. Photo courtesy of Wikimedia.

Our story begins in New Orleans in 1917 when the US Navy shut down Storyville—the city’s famous red-light district—explaining that ‘the District’ was a hazard to the health and morals of its young sailors. But Storyville had kept many New Orleans musicians well fed and dressed to the nines. Lulu White’s Mahogany Hall, a four-story mansion on Basin Street, paneled with exotic woods and inlaid marble, was the flashiest of the era. It had a glitzy mirrored parlor outclassed only by Miss White herself, who wore no less than one diamond ring on every finger at all times—thumbs included. Lulu White had a reputation for hiring New Orleans’ best jazz and ragtime piano players, sometimes called “professors,” to entertain the clientele in her parlor. Both Tony Jackson, who wrote “Pretty Baby,” and the self-proclaimed “inventor of jazz” Jelly Roll Morton worked for her.

Mahogany Hall parlor. Photo courtesy of Wikimedia.

The original Mahogany Hall is gone—replaced by a parking garage. The music lives on in surviving piano works by Jelly Roll Morton such as “Perfect Rag,” heard here performed live by the piano duo of Dick Hyman and John Sheridan on the stage of The Landing.

Lulu White adopted her young nephew Spencer Williams when his mother died, and he grew up in Mahogany Hall. As a boy, he’d fall asleep to the sounds of ‘the Professor’s’ ragtime piano floating up the stairs to his bedroom. Williams soon became a well-known piano player himself, and wrote numerous classic jazz standards, including “Mahogany Hall Stomp,” named after his aunt’s notorious establishment. On this radio show, trumpet icon Doc Cheatham joins The Jim Cullum Jazz Band to recall Louis Armstrong’s popular 1930s recording of Spencer Williams’ timeless composition.

Nightclub culture blossomed in Chicago in the early 1920s, fueled by the “Great Migration” of African Americans from the South who headed North, hoping for less oppression and more opportunity. Even a decade earlier, the area known as “The Stroll” along South State Street in Chicago was a hot spot for black entertainment. At the time, some 500 saloons, 15 gambling houses, 6 variety theaters, 56 poolrooms and 500 bordellos in the area offered entertainment for patrons and jobs for jazz musicians.

Lil Hardin's Band at The Dreamland, 1919. Photo courtesy of Chicago Jazz Archive.

It was in the early 1920s with King Oliver, Louis Armstrong and Earl “Fatha” Hines playing on the South Side that the jazz scene there exploded. Bandleader Eddie Condon said, “you could hold a trumpet in the air and it would play itself.” There was a long string of highly successful clubs built around jazz music on the South Side—The Royal Gardens Café, The Dreamland, The Lincoln Gardens, The Savoy Ballroom and The Grand Terrace—to name only a handful. The Lincoln Gardens’ claim to fame was the world’s first fully formed New Orleans jazz ensemble, King Oliver and his Creole Jazz Band, playing nightly on the bandstand. An enormous mirrored glass ball hung over the dance floor and dazzled the dancers.

In those days of hardline segregation, the few clubs opening their doors to a mix of black and white patrons were known as “black and tans.” By the mid-20s, the Sunset Café was the hottest “black and tan” club in town. Louis Armstrong held forth seven nights a week, often playing until three or four o’clock in the morning. Promoter Joe Glaser, who would later become Armstrong’s personal manager, booked the acts at The Sunset. You can visit this important site in jazz history at East 35th and South Calumet in Chicago. The last known use of the building was as a hardware store. Our tribute to those memorable nights of jazz on the South Side is “Sunset Café Stomp,” a composition written and recorded by Louis Armstrong and his Hot Five in 1926. Our version features The Jim Cullum Jazz Band augmented with Bay Area cornetist Leon Oakley and Chicago tuba player Mike Walbridge.

Earl Hines. Photo courtesy of Earl Hines and Stanley Dance Collection.

The Sunset Café closed its doors in 1937 and re-opened as the Grand Terrace Ballroom. It was renowned for lavish floorshows featuring piano man Earl Hines, sitting center stage at a shiny, white grand piano. Hines said that Al Capone, who toured the South Side in a seven-ton armored limousine, was a regular visitor. According to Hines, Capone would show up at the Grand Terrace with his bodyguards, order the doors closed, hand out hundred dollar tips and politely insist that the musicians play his favorite tunes. In spite of frequent shoot-outs and police raids, glamorous North Side society figures were regulars at the Grand Terrace. The music, under the direction of bandleader Earl Hines, was as spectacular as the floorshows and at least as fascinating as the gangsters. On this broadcast, we pay tribute to Hines and the Grand Terrace with a tune Hines wrote with James R. Mundy titled, “Cavernism,” here featuring pianist Dick Hyman with Jim Cullum and his Band.

Bennie Moten was a pioneer of the freewheeling, blues-based sound of Kansas City jazz. He formed his first band in 1921. By 1929 Moten had picked up most of the players in the legendary “territory band” known as Walter Page’s Blue Devils, including Bill Basie (later known as ‘Count’ Basie) on piano, blues singer Jimmy Rushing and trumpeter Hot Lips Page. All were destined to achieve far greater fame than the trailblazing bandleader Bennie Moten. In the 30s Count Basie emerged as the group’s leader and the Basie Band became a fixture at the Reno Club on the corner of Cherry and 12th Street in Kansas City. In late night, coast-to-coast live radio broadcasts from the club, Basie often featured “Moten's Swing” in tribute to his mentor, a number heard here performed by The Jim Cullum Jazz Band.

During the peak of its popularity, more than 50 jazz clubs could be found within six blocks near the intersection of 18th and Vine in Kansas City. The Reno Club, the Subway Club, Lucille’s Paradise Band Box, the Hole in the Wall and the Hey Hey Club were among the most popular.

Jam sessions were a way of life for musicians in Kansas City. Stories survive of legendary sessions lasting for days, with intense “cutting contests” between dueling saxophonists. Charlie Parker, Coleman Hawkins, Lester Young and Herschel Evans are a few of the heavyweight musicians known to have faced off against each other in Kansas City jam sessions.

.jpg)

Mary Lou Williams. Photo courtesy of Library of Congress.

There was one much-in-demand pianist who stood out in this very male world. Mary Lou Williams came to K.C. with The Clouds of Joy, a band led by her husband Andy Kirk; she went on to develop a high-powered reputation as a pianist, music arranger and composer. In tribute to Williams, The Jim Cullum Jazz Band and piano master Dick Hyman play her best known tune “Roll 'Em,” a Boogie-Woogie number that won the Benny Goodman Orchestra a hit record. Williams said she wrote the tune in memory of Kansas City bluesman Big Joe Turner, who sang the blues from behind the bar as he served drinks to his customers.

A decade after the heyday of the K.C. jazz scene, the hottest and coolest place in the jazz world was New York’s West 52nd Street. The biggest draw on ‘the Street’ in the 40s was a singer who wore a white gardenia in her hair. Billie Holiday, nicknamed “Lady Day” by Lester Young, made the tune “Easy Livin'” famous working with pianist Teddy Wilson at Café Society on Swing Street. Our rendition on this broadcast features the soulful New Orleans jazz and gospel singer Topsy Chapman with Canadian tenor saxophonist Brian Ogilvie.

“The Music Goes 'Round and ‘Round” was introduced on 52nd Street in 1935. Guitarist, singer and raconteur Marty Grosz says, “The number swept the country after its introduction by a couple of nuts named Riley and Farley and their Onyx Club Orchestra. The minute they came up on the stage, out came the soda water siphons, out came the pies, and it was the Two Stooges (instead of Three) in this case.”

Cotton Club ad, 1937. Photo courtesy of blackpast.org.

644 Lenox Avenue in Harlem was the original home of the most notorious of all jazz nightclubs. The Cotton Club was run by gangsters with a firmly enforced “whites-only” policy. The Cotton Club drew the cream of New York society to its shows; and in spite of the racism and hard core gangster management, the club popularized black culture with white audiences. Some of the best music of the early twentieth century debuted on the Cotton Club stage. Louis Armstrong, Ethel Waters and Duke Ellington were all frequently on the bill. During his four-year tenure as conductor of the Cotton Club Orchestra, Duke Ellington wrote his “Black and Tan Fantasy.” The dirge-like opening theme, reminiscent of a New Orleans jazz funeral, gives way to 12-bar blues in both major and minor keys, effectively mixing together dark and lighter moods. The tune was adopted as the anthem of the Harlem Renaissance.

In the mid-to-late 40s, while 52nd Street continued to draw crowds on the East Coast, the West Coast experienced a classic jazz revival harking back to the very, early New Orleans-style of King Oliver and Jelly Roll Morton. Cornetist Lu Watters and his Yerba Buena Jazz Band broadcast live their raucous sound from the Dawn Club south of Market Street in San Francisco. The music became so popular several clubs flourished in the Bay Area. At the Club Hangover on Bush Street, Earl Hines fronted his Dixieland All-Stars. Kid Ory played at the Green Room. A few years later Lu Watters opened Hambone Kelly’s in El Cerrito across the bay. After Watters retired, his trombonist Turk Murphy opened a series of nightclubs under the name Earthquake McGoon’s, the most famous on Clay Street in San Francisco. Host David Holt recalls the club going strong when he dropped by in the 1960s.

Lu Watters and Turk Murphy not only revived and popularized a lost art, but they also wrote many new compositions and arrangements in the traditional New Orleans style, among them “Sage Hen Strut,” performed this week by an augmented Jim Cullum Jazz Band.

.jpg)

In 1963 when Jim Cullum Sr. and Jr. opened The Landing on the Paseo del Rio (River Walk) in San Antonio, their establishment was the only sign of life on the river for several blocks in either direction. Shortly before the passing of Jim Sr. in 1973, a jam session at the Landing featuring classic jazz giants Ralph Sutton, Bob Wilber and Yank Lawson was captured on audiotape, a fragment of which is included in our show. The concluding tune, “Royal Garden Blues” featuring Australian cornet master Bob Barnard, is an example of the work of the present-day Jim Cullum Jazz Band as featured at The Landing.

Photo credit for homepage image: Topsy Chapman. Photo courtesy of the artist.

Text based on Riverwalk Jazz script by Margaret Moos Pick ©1997