In Jazz Age Harlem the rise of black culture produced talents like Langston Hughes and Duke Ellington. But this ‘Black Renaissance’ wasn’t limited to men.

A largely unsung group of black women were a driving force in the movement. They wrote poetry, managed literary journals, and held salons that nurtured Harlem's great social revolution of the 1920s.

Special Web Exclusive:

This week on Riverwalk Jazz singer and actress Carol Woods, known for her many roles on Broadway and in the movies, joins us to remember these women and celebrate their work. The Jim Cullum Jazz Band and their guests perform the music of Duke Ellington and James P Johnson.

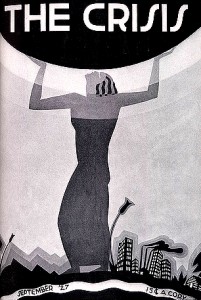

A magazine called The Crisis played a major role in the Black Renaissance of the 20s. Selling 100,000 copies a month, it gave voice to young writers like Langston Hughes and Zora Neale Hurston. W.E.B. Du Bois launched the magazine under the auspices of the NAACP, but it was a dedicated woman, working in his shadow, who ran The Crisis and shaped its literary style.

Jessie Redmon Fauset is remembered today as the "Midwife of the Harlem Renaissance." A poet and novelist herself, she shouldered the lion’s share of the work of publishing The Crisis. Another great labor of love for her was The Brownie’s Book—a magazine for "children of color"—with poems, African folk tales and stories about black leaders.

Opportunity, African American Journal. Image courtesy Williamson Collection, Moorland-Spingarn Research Center.

Helene Johnson began winning literary prizes when she was still a teenager. In 1926 her work was recognized by James Weldon Johnson and poet laureate to be, Robert Frost, when she won a poetry competition sponsored by the African American journal, Opportunity.

Johnson grew up in a Boston suburb surrounded by her extended family of strong women. Drawn to Harlem in the 20s she moved to New York with her cousin Dorothy West, who would become a leading novelist of the Renaissance. Johnson fell in love with Harlem street culture and nightlife and wrote about them in her poetry.

Thanks to a real estate bubble that burst in the early part of the century, some 200,000 African Americans could afford to live in Harlem in the 1920s. The neighborhood between 114th and 156th Streets had so much going on, it was a popular pastime to stand on a street corner and watch celebrities go by. Fats Waller, Fletcher Henderson and Ethel Waters all lived within a few blocks.

There were plays and lectures at the YMCA. The Friday night late show at the Lafayette was a local tradition. And poetry readings put on by Miss Ernestine Rose at the New York Public Library were a popular hit. Great parties in private homes were reported in-full in the society pages of the Harlem press. No one could beat the sparkling 'Harlem-ese’ of gossip columnist Geraldyn Dismond. With her ‘marcelled' waves and diamond earrings, she was a fixture at these salons.

Of all the salons in Jazz Age Harlem, celebrity heiress A’Lelia Walker’s were the most extravagant and the most decadent. Decked out in her silks and furs, A’Lelia stood a majestic 6 feet tall.

No one could stop gossiping about the night she threw a party and segregated her guests, serving pig’s feet and bathtub gin to her white friends, while next door, black party-goers dined on caviar and champagne. Some black intellectuals considered A’Lelia’s grand salon a sideshow that undermined the seriousness of the movement. But Harlem’s "poet laureate" Langston Hughes was one of her admirers.

Poet Gwendolyn Bennett made her debut at a 1924 Civic Club dinner in New York. Meant to be a book release party celebrating the publication of her friend Jessie Fauset’s first novel, it turned into a coming-out party for several young black writers, including Bennett. The poem she read that night, “To Usward,” became an anthem of the "New Negro" movement.

As with many of the women poets of the era, not much is known about why Elma Ehrlich Levinger wrote the poetry she did. What is surprising to us today is that she was a white, Jewish woman and a prolific writer of books about her faith. But in March 1924, a powerful poem she wrote about black experience, “Carry Me Back to Old Virginny” appeared in The Crisis.

Women poets of the Harlem Renaissance wrote about nature, romantic love and motherhood, but their racial identity was always at the forefront of their work. They embraced the common threads running through all the ideas and entertainment of Jazz Age Harlem—a sense of pride, political assertiveness, and pure delight in the time and place.

Photo credit for Home Page: Flappers in Harlem, James Van Der Zee.

Text based on Riverwalk Jazz script ©2010 by Margaret Moos Pick