In 1917 the first jazz recording was made, and to everyone's surprise it became a huge popular success. This edition of Riverwalk Jazz celebrates the musicians who made that hit record—the Original Dixieland Jazz Band, affectionately known as the ODJB.

"Livery Stable Blues" label. Image in public domain.

It's hard to imagine a time when jazz was not a part of the American experience. Even now, more than 100 years after the mythic Buddy Bolden blew his horn in New Orleans, arguments are as heated as ever as to when and where jazz was born. Nonetheless, at least one fact remains unchallenged in jazz history. Almost a century ago, five extroverted white jazz musicians recorded two numbers for the Victor Talking Machine Company on February 26, 1917—and “Livery Stable Blues” with “Dixie Jass Band One-Step” on the flip side is recognized as the first commercially released jazz record in history. The silly, if not downright crude, “Livery Stable Blues” took off like a rocket and launched a cultural revolution.

Frequently dismissed as white musicians of little merit who cashed in on black music, recordings of the Original Dixieland Jazz Band nonetheless hold their own some hundred years later. Calling themselves ‘The Creators of Jazz,” at a time when the new music was literally coming up out of the ground all over the country, did not help their reputation. The ODJB was not the only boastful group in the business. From ‘Inventor of Jazz’ Jelly Roll Morton to ‘King’ Oliver and ‘Empress’ Bessie Smith, everyone laid claim to lofty titles.

ODJB members. Photo courtesy redhotjazz.com

ODJB band members came out of New Orleans where several played in the racially integrated Papa Jack Laine band, performing for parades and dances. Luck smiled on March 3, 1916, when they opened at Schiller's Cafe in Chicago, under the name Stein’s Dixie Jazz Band. They were a hit and the group cloned itself, bringing in clarinetist Larry Shields and drummer Tony Sbarbaro from New Orleans; they began calling themselves The Original Dixieland Jass Band. Theatrical agent Max Hart introduced the boys to New York, booking them into the spectacular Reisenweber’s Cafe on Columbus Circle, where on January 27, 1917 The Original Dixieland Jass Band stomped off a firestorm of syncopation.

The New York Times touted their arrival as "the first sensational, musical novelty of 1917. The jazz band is the latest craze that's sweeping the nation like a musical thunderstorm, and it's given modern dancing new life and a new thrill." The brashness, energy and urgency of the music stunned the crowd at Reisenweber's. No one in world weary New York had ever heard anything as lively, or as loud.

The Original Dixieland Jazz Band. Photo courtesy last.fm.

Within a week record companies were sparring over the ODJB perplexed by their popularity but determined to cash in on the phenomenon. The Victor Talking Machine Company won the bidding war and in March 1917 released "Livery Stable Blues," the first jazz record ever, and perhaps the first and last example of "barnyard jazz." "Livery Stable Blues" was an instant success, selling hundreds of thousands of copies, outstripping John Phillip Sousa and Enrique Caruso in sales.

Jim Cullum says,

“It's interesting that on the flip side was a piece called, "Dixie Jass Band One-Step." The ODJB thought that piece would be their big number; it would be the hit. But you never know about these things. Now oddly enough, "Livery Stable Blues" has completely faded into obscurity and is never played anymore, and "Dixie Jass Band One-Step" is played by traditional bands all the time.”

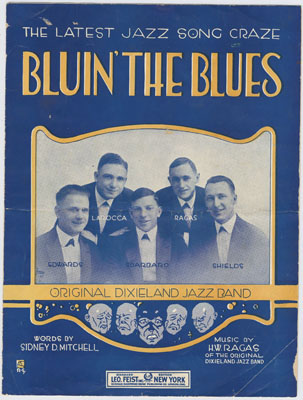

"Bluin' the Blues" sheet music. Image courtesy musicatthemint.org

In January 1917 when “Livery Stable Blues” came out, many Americans were in deep denial over the country's inevitable entry into World War I. Anxious about world events, people turned to music of all kinds, and every city had society orchestras, marching bands, vaudeville floorshows and string ensembles. From smart Broadway songs played on parlor pianos to the blues of the Deep South, America's musical menu was rich.

The term "jazz" (or "jass," as the ODJB first spelled it) was yet to be in wide use to describe a type of music. The term had previously come into limited use as sexual innuendo or as a polite newspaper article of the time expressed it, a synonym for "enthusiasm." Even the Crescent City was reluctant to claim "jazz.” As one writer mused in a New Orleans newspaper in 1918,

“Jazz is like an indecent story, except syncopated and counterpointed. Like the improper anecdote, jazz used to be listened to behind closed doors and drawn curtains, but like all vice it grew bolder and is tolerated because of its oddity.”

But oddity, combined with talent, imagination, resourcefulness, good timing and incredible luck landed five unsuspecting self-taught New Orleans musicians in the history books. In the second decade of the 20th Century, members of The Original Dixieland Jazz Band, and many other musicians both black and white fascinated with the new music sweeping the country, traveled north from New Orleans to New York, Kansas City, and especially Chicago. For the ODJB, their nine-month stay in Chicago was critical to their success. There they honed the technique they had learned in New Orleans into a unified ensemble style. As biographer H.L. Brunn writes, "The artists finally mastered their medium."

Nick LaRocca. Photo courtesy Wikipedia.

When the ODJB made their New York debut they played a sizzling-hot number written by cornetist Nick LaRocca, "Tiger Rag." It's an energetic, multi-theme tune that continues to be widely performed today. Yet, there's been great debate about who wrote it. In 1936 New Orleans musician, composer and publisher Clarence Williams publicly declared that "Tiger Rag" sounded a lot like a certain well-known quadrille, a popular folk dance of the day. Nick LaRocca hired a lawyer and dared Williams to prove it. Williams backed down. Then in 1938 Jelly Roll Morton got in the game, and claimed he wrote it. Finally LaRocca admitted that the tune is derived from three well-known melodies, including the children's rhyme, "London Bridge is Falling Down." The biggest surprise came from ODJB trombonist Eddie Edwards. Some 20 years later he claimed that he came up with certain phrases of "Tiger Rag" based on Beethoven's 4th Symphony.

"Tiger Rag" sheet music. Image courtesy moblog.whmsoft.net

Initially the ODJB was set up as a cooperative enterprise with a share and share-alike arrangement among all the band members. Technically there was no leader, but early on cornetist Nick LaRocca emerged as the one to take care of business. Dominick James LaRocca, always known as Nick, had a show-biz promoter's intuition. He knew what the public wanted and how to serve it up. He had a head for business and was a shameless opportunist who could be ethical one minute and conniving the next. As the years progressed, "cooperative" was not the word to describe ODJB band members. Copyright disputes, booking agent battles, personality clashes and drinking problems plagued the band. Squabbling got in the way of creativity and made it difficult for the Band to adapt to lightning-quick developments in jazz.

Nonetheless the ODJB created a sizeable body of work and left a substantial legacy. On this radio show, The Jim Cullum Jazz Band plays the best-known and most-often recorded of the ODJB’s tunes, including "Fidgety Feet," "Ostrich Walk," "Bluin' The Blues" "Clarinet Marmalade," “Tiger Rag” and "At the Jazz Band Ball." These tunes were cornerstones of key bands of classic jazz, among them Bix Beiderbecke and the Wolverines and the Bob Crosby Bob Cats.

Photo credit for Home Page: The Original Dixieland Jazz Band. Photo courtesy last.fm

Text based on Riverwalk Jazz script by Margaret Moos Pick © 1997