Riverwalk Jazz celebrates Texas Roots in Jazz and Blues, and pays tribute to native sons— bluesman Lead Belly, ragtime icon Scott Joplin and trombone maestro “Texas Big T” Jack Teagarden.

Lead Belly, the fabled American bluesman and folk musician grew up on a freehold farm in East Texas on the Red River bottomlands, where he was known as Huddie Ledbetter. In and out of prison, this “bad man minstrel” knew so many songs, they called him a “human jukebox.” It’s said he sang his way out of Angola State Penitentiary by charming the warden with his endless repertoire and driving 12-string guitar playing style. Lead Belly sang it all—from field hollers to work songs. He sang cowboy songs like, “The Old Chisholm Trail.” Folk songs, like “The Rock Island Line.” Country blues like, “Good Mornin’ Blues.” Lead Belly not only sang these pillars of traditional music, but he owned them; he made them his own.

Born in 1890 in Wortham, Texas about 80 miles south of Dallas, Blind Lemon Jefferson won his place in history with a plaintive, moaning vocal style, intricate fingerings on his guitar, and lyrics like “There’s One Kind Favor I Ask of You, See That My Grave’s Kept Clean.” Bob Dylan successfully covered this Blind Lemon Jefferson song in 1966, reviving interest in the bluesman.

Even before World War I, a deep, rich strain of Texas blues—thick as Texas crude—emerged from the farmlands and backwoods cabins of East Texas. Fueled by a migrant black population of farm hands and itinerant musicians, Texas blues spread throughout the Southwest, then headed north into the Great Plains states. There were singer-songwriters like Ragtime Texas Thomas, who wrote the “Fishin’ Blues,” re-invented by Taj Mahal in the 60s.

In 1920s Dallas, honkytonks in the city’s Deep Ellum neighborhood were a great place to hear the blues. Lead Belly and Blind Lemon Jefferson were the area’s street singers and stars; and a young T-Bone Walker learned his stuff hanging out with these masters.

Boogie Woogie came up out of the ground in the piney woods of East Texas. Lumber camp owners built barrelhouse sheds, serving up cheap booze and hot blues, as a way to keep their workers from running off to the nearest bar for a night on the town. An upright piano was standard equipment in these joints. After ten hours on the job, hard-working loggers let off steam drinking beer and dancing to a Boogie Woogie beat.

Lead Belly said he first heard Boogie Woogie in Cottle County, Texas in 1899 and imitated its rhythmic feel and bass line on his guitar. In the turpentine country of East Texas, Boogie-Woogie was known as “Fast Texas Piano.”

The tune “Hop Scop Blues,” also called “New Orleans Hop Scop,” was composed by George Thomas in 1911 and is recognized as one of the earliest Boogie Woogie tunes published on sheet music. Though it’s a good bet the characteristic “boogie” bass line with its familiar arpeggiated major triads was in use in Lead Belly’s time and earlier.

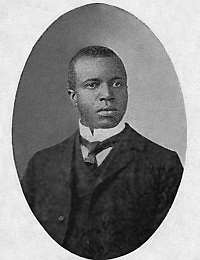

Scott Joplin photo courtesy Wikimedia

Scott Joplin, the father of Ragtime, born in Texarkana, Texas, published some of his first compositions in Temple, a small town near Waco. Joplin wrote one of these pieces in commemoration of a spectacular event, staged in nearby Crush, Texas by an eccentric promoter, Mr. Crush. “I remember the story well because it was part of our family lore,” says series host David Holt. “My great-grandfather Holt was from the next town over, West, Texas.” Scott Joplin was touring the state with the Texas Melody Quartet and got word of Mr. Crush’s plan to stage a head-on crash of the biggest, most powerful locomotives in the world. It was a massive effort that took months of preparation. They laid miles and miles of railroad track out in the middle of nowhere. They brought in two huge locomotives from opposite ends of the country. Thomas Edison sent down one of his early movie cameras to record the event. Thousands of people came from all over. They had to bring in waiters from St. Louis to cater to the crowds.

Scott Joplin was there as the locomotives came steaming down the track, coming at each other at full steam power. Suddenly there was a tremendous crash and a huge explosion as the steam engines blew up. There was a horrendous sound of metal grinding on metal. Bolts, steel rods and engine parts went flying through the air. By all accounts, it was dangerous, dirty, and for one poor soul—lethal. Scott Joplin’s composition, not destined to be his most famous, was called “The Great Crush Collision March.”

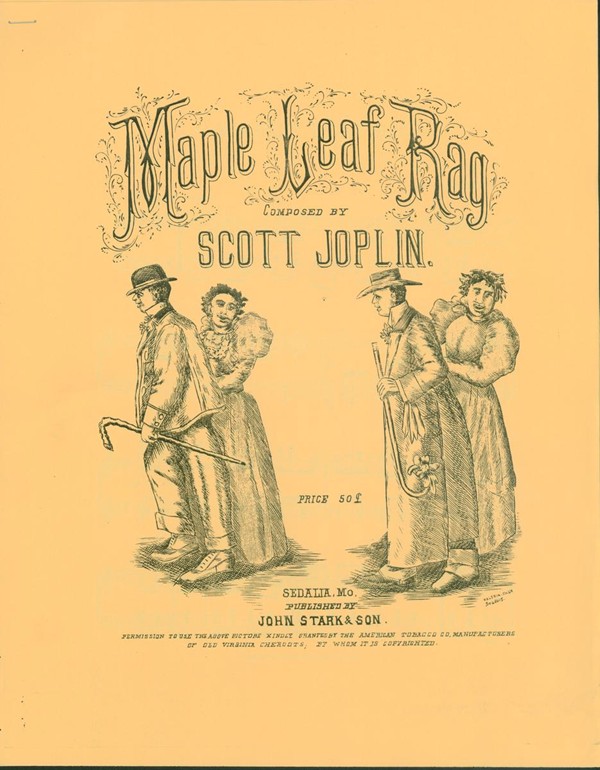

"Maple Leaf Rag" sheet music. Image courtesy ragtimepiano.ca

A few years later while living in Sedalia, Missouri, Joplin hit the big time with a trio of hits: “Maple Leaf Rag,” “Easy Winners” and “The Entertainer.” Joplin’s ragtime compositions on piano rolls and sheet music introduced syncopated rhythm into respectable middle-class parlors for the first time and revolutionized popular music. “Maple Leaf Rag” was an enormous hit, as Americans everywhere kicked up their heels to Ragtime.

Six years after “Maple Leaf Rag” swept the nation Jack Teagarden was born in the tiny town of Vernon, Texas—on the windy flatlands of the southern Texas Panhandle. A natural musician, he was playing the trombone before his arms were long enough to extend the slide all the way. At age sixteen in 1921, he left home for the big city to the south—San Antonio—where he got a job at a roadhouse called the Horn Palace. The place was full of wild animal trophies, stuffed and mounted on the walls. During the day, the joint was a watering hole for big-time ranchers and politicians, but by night it was a scene out of the Wild West. Ranch hands and off-duty soldiers drank and gambled away their paychecks, and fistfights were a regular part of the entertainment. Jack Teagarden thought he had died and gone to heaven—he was staying up all night playing music and getting paid for it!

On this broadcast, Jim Cullum tells the story of a night of gunplay at the Horn Palace resulting in a murder to which young Teagarden was a key eyewitness. Before the trial, there were threats to Jack from both the authorities and the perpetrator, but the great Texas flood of 1921 washed away the evidence along with most of San Antonio. Jack took advantage of the chaos to make his break for Houston and a new life. There he joined the legendary jazz piano master Peck Kelley, the composer in 1918 of “I'm Gonna Stomp Mr. Henry Lee,” aka “Stomp It, Mr. Kelley.”

Peck Kelley had a reputation for turning down offers no one else could refuse. Born in Houston in 1898, he established his own band Peck’s Bad Boys in and around Houston, and often played at Galveston Bay. Peck had outstanding musicians in his bands, including clarinetist Pee Wee Russell and trombone giant Jack Teagarden. The Big League came calling on a regular basis, but Kelley was not shy in turning down offers from bandleaders Jimmy and Tommy Dorsey, Paul Whiteman, Bing Crosby, and Rudy Vallée, among others. Late in life Peck said, “You know, people think it’s strange I didn’t go with the big names in the 30s. Maybe the real reason is that I never felt like I needed to entertain people, I just like to play piano for myself.”

Jack Teagarden early PR photo. Courtesy geocities.com

It wasn’t long before Jack Teagarden made his way to the bright lights of New York City. In a session with jazz violinist Joe Venuti and guitarist Eddie Lang, Jack got his first break recording “She’s a Great, Great Girl in 1928; it would be Teagarden’s first ever recording session. By 1929 Teagarden was in the recording studio with Louis Armstrong whose star was also on the rise. Jim Cullum says, “Louis and Jack were magic together, they inspired each other to new heights.“ “Knockin a Jug” was one of the tunes from those late 20s sessions.

Blues man Robert Johnson wasn’t born in Texas, but the Lone Star State was his stomping ground. He played and sang throughout Texas and made some of his most famous recordings in San Antonio at The Gunter Hotel (not the Bluebonnet Hotel as noted in various histories and on this radio show.) One day in November, 1936, Robert Johnson showed up at the hotel room where Vocalion A&R man Don Law was making field recordings of everything from dance orchestras to yodelers and blues singers. In three sessions in San Antonio, Robert Johnson recorded “Walkin’ Blues,” “Terraplane Blues” and “Crossroads Blues,” later covered by Eric Clapton and Cream in the 1960s. Johnson was so shy he insisted on facing the wall during the entire session.

The story goes that later that night Johnson was picked up for vagrancy and worked over by the cops. Don Law got word of the incident and came down to the station, bailed him out, took him over to a boarding house, gave him 45 cents for breakfast and told him to stay put for the night. Law was sitting down to finish his dinner at the hotel when he got another call. This time, Johnson told him, “I’m lonesome. There’s a lady here and she wants fifty cents and I lacks a nickel.”

Don Albert. Photo courtesy Institute of Texan Cultures

A New Orleans Creole by birth, Don Albert moved to Texas as a teenager and soon became one of the legends of Texas jazz. He was an Armstrong-style trumpet man and played with some of the best players and singers in jazz—Billie Holiday, Ella Fitzgerald, Count Basie and Bunk Johnson. In 1929 Don brought his band into Shadowland, a classy San Antonio nightclub. Jim Cullum says, “Even the bouncers wore tuxedos.” The Don Albert Orchestra had a sophisticated style inspired by Duke Ellington. In the 1930s Don Albert’s outfit was one of the premier bands in the Southwest territory, with a regular live broadcast from Shadowland. Cullum says, “They had a big following all over the Midwest, Florida and even down in Mexico.” Don Albert and his band recorded an original tune, “Deep Blue Melody,” at that same 1936 recording session at the Gunter Hotel as Robert Johnson.

In the 1920s and 30s the merging of Texas Blues with the westward migration of New Orleans jazz gave rise to sophisticated jazz orchestras known as “territory bands.” They traveled a circuit throughout the Southwest, supplying the demand for live entertainment in hotel ballrooms and rooftop gardens. Among the most famous were two bands out of Texas, the Alfonso Trent Orchestra and Troy Floyd’s band. Musicians in these groups developed the seed of what was to flower in Kansas City with Benny Moten’s sound, and the popularity of the Count Basie Orchestra. Jim Cullum’s favorite “hot” band of the era was Jimmy’s Joys. One of their tunes, “Clarinet Marmalade,” is very much in the hot style of Bix Beiderbecke and the Wolverines.

A number of great tenor saxophonists came out of Texas in the 1920s and 30s. Illinois Jaquet and Arnett Cobb grew up in Houston, Budd Johnson emerged in Dallas, Buddy Tate was from Sherman, Texas and Herschel Evans from Denton. Playing in territory bands, they all developed a similar sound. These legendary Texas tenor men were known to ride over a brass section with a big, booming, open sound. Some say this “Texas tenor” sound set the standard for today’s rhythm and blues playing.

When the Depression put most of the territory bands out of business, the musicians gravitated to Kansas City. Some made it big with the Count Basie Band. One of the greatest tenor players on the Basie bandstand was Texan Herschel Evans. On our show this week, Cullum Band reedman Brian Ogilvie celebrates the Texas tenor sound with an Evans original, “Doggin' Around,” a hit for the Basie Band.

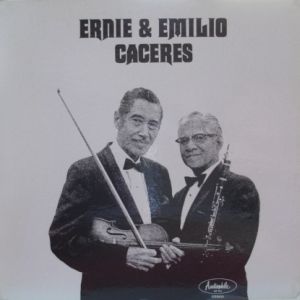

Ernie and Emilio Caceres. Image coutesy cdandlp.com

San Antonio has a long tradition of homegrown hot jazz. With its large Hispanic population, it’s natural that a couple of the greatest jazz instrumentalists of the Swing Era were Hispanic musicians from San Antonio, Emilio and Ernie Caceres. Emilio was one of the top jazz violinists of the era, some say on a par with Joe Venuti. Though Emilio refused all offers to play in New York. Instead he led his big band in San Antonio and on a weekly radio show on WOAI. However, Ernie Caceres left Texas as a young man and made a name for himself playing clarinet and baritone sax in New York with Tommy Dorsey, Jack Teagarden and Woody Herman. It was Ernie’s long-running gig with the Glenn Miller Orchestra that made him a national star. As a tribute to the Caceres family, Jim and the Band play their signature tune, “Humoresque in Swing Time.”

Photo credit for Home Page: Huddie 'Leadbelly' Ledbetter courtesy somethingelsereviews.com

Text based on Riverwalk Jazz script by Margaret Moos Pick ©1994