The romantic sound of Bobby Hackett's cornet set the mood for millions of love scenes across America in the 1950s. His lyrical style and polished, near-perfect execution made him one of the greatest ballad players in the history of jazz. Hackett’s playing has reminded some listeners of cornetist Bix Beiderbecke, but his first inspiration came from jazz trumpeter Louis Armstrong. Joining us this week to honor the musical legacy of Bobby Hackett is another world-class cornetist, Australian Bob Barnard. Also on this broadcast is actor Eli Wallach, a legend of American theater and film, who portrays Bobby Hackett with snapshots of first person accounts of the jazzman’s life.

Cornetist Bob Barnard is well known worldwide as one of Australia’s greatest jazz exports. He came up through the ranks of the post-WWII Australian jazz movement. He spent his early career in Melbourne, then joined Graeme Bell’s storied band in the 1960s and moved to Sydney. Later he formed his own band there. Jim Cullum says, “Bob Barnard is my favorite cornetist… I’ve been a fan of his for years, and we always have a terrific time playing together. Bob has a great affinity for Bobby Hackett’s style. There isn’t anyone else who can do a better job on this material.”

Bobby Hackett was born in Providence, Rhode Island in the winter of 1915 into a family of nine children; his father worked as a blacksmith. It was the sound of a Louis Armstrong recording being played in a Providence department store that made Bobby want to take up the cornet. He was twelve years old when he bought his first horn at a pawnshop. His mother couldn’t stand the racket of his practice sessions and would hide his horn to keep him from playing it. Bobby would search the house until he found his instrument; then he’d practice as much as he could until his mother hid it again.

Bobby Hackett photo courtesy Wikimedia.

As fate would have it, Hackett’s first professional gig was at age sixteen sitting in with Cab Calloway’s Orchestra. Cab was performing a one-nighter at a local ballroom in Hackett’s hometown when one of Cab’s trumpeters fell ill. Bobby showed up at the concert to watch the great showman perform, but when Cab found out Bobby knew how to play cornet he was invited to sit in. Hackett couldn’t read music, and the notes flew by. The trombonist sitting next to him on the bandstand had a pint of gin, and together they swigged it to keep their morale up. At the end of the evening, Cab gave Bobby twenty-five dollars—a week’s pay for an adult at the time, and more money than Bobby had ever had ever held in his hands. Back at home, Bobby Hackett proudly laid the cash on the kitchen table, but his mother accused him of stealing it. At last he was able to convince her he’d earned the money playing his horn, and the cornet was no longer just noise to his mother.

Bobby Hackett paid his dues playing summer resorts and Boston speakeasies, then made it to New York City in the mid-1930s. Bobby recalled having stage fright, just being in New York, where so many great jazz artists held forth. He said, “When I first went to the Famous Door where Pee Wee Russell was playing with Louis Prima, I got so scared I got drunk and went back home to Boston the next day.“ Eventually he worked up his nerve, went back to New York, and connected with bandleader Eddie Condon. Hackett soon became a fixture in Condon’s bands and over the years made numerous recordings in his studio bands. One of these, Bixieland from 1955, is a tribute to Bix Beiderbecke. When they cut the record, Bobby was signed with Capitol Records, and Eddie Condon was signed with Columbia. To get around hassling with record label politics, Hackett played the session under a fake name. To this day, “Pete Pesci” is credited with playing cornet on Bixieland. The real Pete Pesci, not a musician at all, was the general manager of Condon’s jazz club in Greenwich Village.

Jim Cullum says about Hackett’s recording of “I'm Comin' Virginia” from Bixieland (excerpted on our show this week), “it’s one of Hackett’s crowning achievements, and a great work of art, an example of Hackett’s fully developed lyricism. He first emerged as a Bix Beiderbecke disciple. His tone and lyricism is Bix-ish, but later Bobby perfected his own instantly recognizable personal style.”

.jpg)

Ernie Caceres, Bobby Hackett, Freddie Ohms and George Wettling, Nick's, New York City, 1940s. Photo by William P. Gottlieb, courtesy Library of Congress.

Hackett was a powerful force on the New York jazz scene in the 1940s. His sessions with Condon helped mold Hackett’s style; in turn Hackett influenced the whole Condon school. Many of these recording sessions had an informal “jam session” feel, similar to the style Jim Cullum, Bob Barnard and the Band get on the version of “Royal Garden Blues” heard here. Jim Cullum says that if it weren’t for Hackett’s fluid style of ballad playing, “a lot of classic jazz bands like ours wouldn’t have ballads in their repertoire at all. In the same way that Louis Armstrong taught the world to swing, Bobby Hackett taught the world how a jazz ballad should sound.” As an example, Bob Barnard and the Band offer another of Hackett’s favorites, “When Your Lover Has Gone.”

Bobby Hackett first met Jackie Gleason in 1942 during the filming of the Glenn Miller biopic Orchestra Wives. At the time, Gleason told Hackett he wanted to record his smooth cornet playing with a string section. A decade later, Gleason realized his dream with a series of sixteen best-selling LP albums, two of which, For Lovers Only and Music, Martinis and Memories, were hugely successful and garnered a wealth of radio airplay through the decades; these tracks ultimately became staples on Muzak. Jackie Gleason’s hit albums featuring Bobby’s romantic cornet solos were developed and conducted by Hackett, though Gleason received much of the credit.

Eli Wallach photo courtesy Wikimedia

In 1972 Whitney Balliett interviewed Bobby Hackett at his home in Cape Cod. Bobby and his wife Edna had left New York for life in the country. Late in life, a recovered alcoholic and diabetic, he continued his long-running love affair with music. In the interview, Hackett reminisced about his hero Louis Armstrong. On this week’s radio show, the renowned actor Eli Wallach brings to life excerpts from that interview:

“He..taught me by example that the key to music, the key to life, is concentration. When I solo, I listen to the piano and the other instruments and I try to play against what they’re doing. But the ideal way to play would be to concentrate to such an extent that all you could hear was yourself, which is something I’ve been trying to do all my life, to make my music absolutely pure. In this business you either hit home runs or you strike out. Anything in between—you’re just second-rate.”

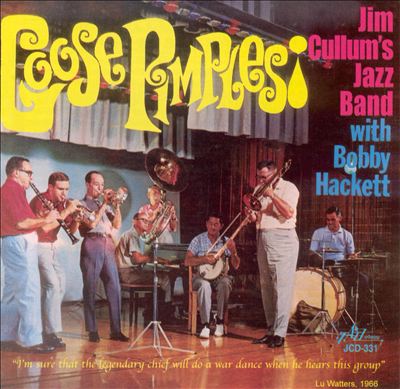

Goose Pimples album cover courtesy Jim Cullum Jr.

More about this week’s radio playlist:

“Goose Pimples,” from the playing of Jazz Age cornet genius Bix Beiderbecke, is also the title tune of an album Jim Cullum and his father recorded with Bobby Hackett in San Antonio in 1967. Jim remembers what a thrill it was to work with Hackett: “Bobby’s personality matched his music—he was a sweet guy, a gentle and kind person, very giving in spirit and encouraging to young musicians like myself. His music was lyrical, thoughtful and very sensitive.”

Jim Cullum recounts how the San Antonio recording session came about as a result of Jim Sr. playing a gig at Peanuts Hucko’s nightclub in Denver. Bobby Hackett also happened to be playing there, along with pianist Dave McKenna. At the club, Jim Sr. invited Hackett to come down to San Antonio to make a recording with the Happy Jazz Band, as the Cullums’ band was then known. “The album was cooked up in a very short time,” says Jim Jr.

“Yellow Days” is a tune Hackett loved to play as a jazz ballad. Created by Mexican composer Alvaro Carrillo in 1964, it is well-known in the Latin music world as “La Mentira” (The Lie). Percy Faith’s ‘easy listening’ version was a hit in the early 1960s, but it entered the jazz world via Bobby Hackett’s 1969 recording.

“'S Wonderful” is a Gershwin standard Hackett played often. “Albatross,” composed by Dick Carey, is a tune from Hackett’s time with the Eddie Condon mob, and Hackett later recorded it for his series on Capitol.

In the summer of 1941 Hackett joined Glenn Miller as a rhythm guitarist. His fans thought it was insulting that Miller didn’t have him playing cornet. No one knew that Bobby was recuperating from dental surgery at the time. When Hackett got back to the cornet, he and Miller played duets together. Hackett created the oft-quoted cornet solo on the 1942 Glenn Miller band mega-hit, “A String of Pearls.” Hackett said his solo began as an improvised exercise on the 12-bar blues.

“Bobby Hackett Waltz” was composed by frequent Riverwalk Jazz guest artist Dick Hyman in tribute to Hackett’s lyrical approach to melody.

“Big Butter and Egg Man” is from Louis Armstrong’s Hot Five recordings of the 1920s. The Hot Five and Hot Seven series rank among the most influential bodies of work in jazz history.

Photo credit for Home page: Bobby Hackett courtesy allaboutjazz.com

Text based on Riverwalk Jazz script by Margaret Moos Pick ©1993