Red Hot Peppers Victor record label. Image in public domain.

This Riverwalk Jazz radio broadcast, Red Peppers and Hot Wax, is one of a two-part series exploring the evolution of ‘studio bands’ in jazz. The ‘Red Peppers’ of the title refers to Jelly Roll Morton’s seminal recording group working under the name The Red Hot Peppers for the Victor label between 1926 and 30. ‘Hot wax’ is a reference to the early method of using wax platters in the recording process; the recording stylus (or needle) would cut grooves in the hot wax, and it would then go through several stages of electrolysis to make the metal master from which discs were stamped.

The early 1920s saw the rise of the recording industry in America, and Victor, Columbia, Brunswick and Okeh were the four giant record labels running the business. Working in makeshift studios, Jelly Roll and Satchmo, Bix and Fats made their magic and left a legacy of classic recordings still considered blueprints for jazz musicians today. Audio engineers pioneered the development of recording techniques, often making it up as they went along. They gathered musicians around megaphone-shaped horns and draped pianos with cloth to make the sound softer. They attached tiny acoustic horns to violins to amplify the sound. Canvas tents were pitched over recording spaces filled with musicians to eliminate ‘room echo.’ Bass drums confiscated at the studio door were exchanged for woodblocks, cowbells and suitcases.

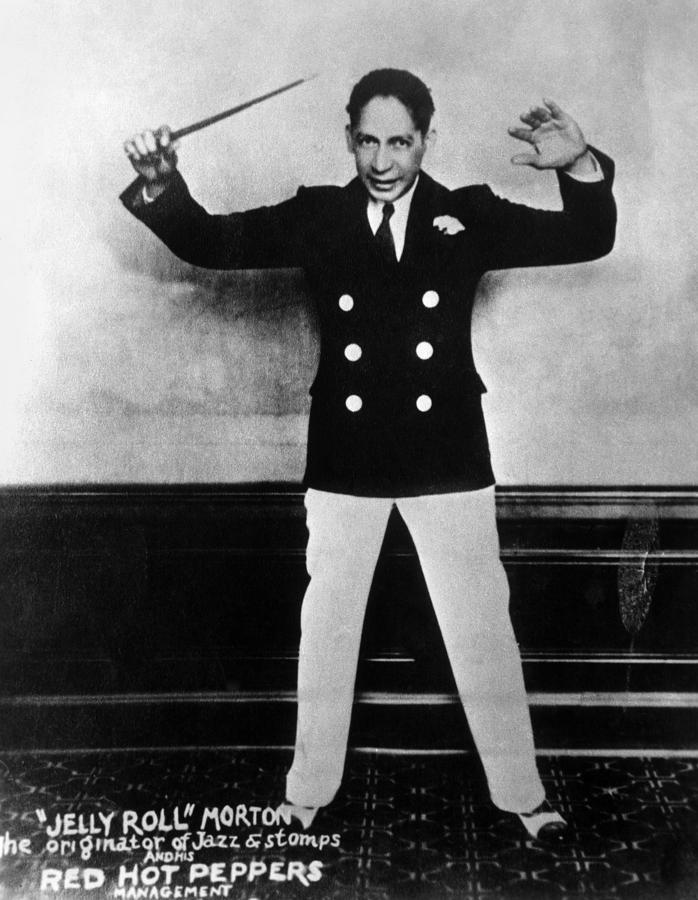

Jelly Roll Morton's Red Hot Peppers, 1928. Photo courtesy of redhotjazz.

Engineers dared to put a pillow under the stomping foot of the first great jazz composer and record producer, Ferdinand “Jelly Roll” Morton. Drummer Baby Dodds recalled the early Chicago sessions produced by Morton. “The Red Hot Peppers weren’t a working band,” he said. “When Jelly Roll gave us a ring, we met for the first time at the rehearsal. We all knew each other from New Orleans, of course, but those rehearsals and the record sessions Jelly called were the only times we got together to play as a band. Everyone had to do just what Jelly wanted him to do. During the rehearsal he would say, ‘Now that’s just the way I want it on the recording.’ And he meant it. You did what Jelly wanted you to, no more, no less.”

Years later, Omer Simeon, the great New Orleans clarinetist, recalled, “We’d have a couple of rehearsals at Jelly’s house before the recording date and Walter Melrose, the publisher, would pay us five dollars a man. Jelly Roll’s recording sessions were the only ones where I got paid for a rehearsal. It was time and money well spent.”

No one knows for sure how Jelly Roll Morton ended up with a contract to record for Victor. So-called “race records” were the bread and butter of companies like Okeh, Brunswick and Gennett, but the Victor label, then the most technically advanced recording company in the country, showed little interest in recording black artists. Nonetheless, in the fall of 1926 Morton signed a major recording contract with the Victor Recording Company.

"Black Bottom Stomp" record label. Image in public domain.

On September 15, 1926 at 9:00 o’clock in the morning, Morton strolled into the Webster Hotel on Chicago’s North Side with his hand-picked battery of New Orleans musicians, among them clarinetist Omer Simeon, trombonist Kid Ory and trumpeter George Mitchell. At later sessions, brothers Johnny and Baby Dodds would join the group. Over the course of little more than a year, Jelly’s Red Hot Peppers recorded several Morton originals including the remarkable piece “Wild Man Blues.” Heard on this broadcast is a duet on ‘Wild Man’ with bandleader Jim Cullum on cornet and John Sheridan on piano. Also heard is the original 1926 Victor recording of the Red Hot Peppers band on “Black Bottom Stomp,” followed by a live crossfade into The Jim Cullum Jazz Band going full tilt.

Bandleader Jim Cullum comments on Morton’s Red Hot Peppers’ sessions:

“What’s remarkable to me is that Jelly Roll Morton is the first musician to take complete control over every aspect of a recording session. He saw the value of working out the concept in advance down to every detail. He almost always wrote his own material, and he worked out the instrumentation and the arrangements—from every introduction to every ending phrase. One of the first examples of a full, modern rhythm section with drums, guitar, piano and a string bass replacing the older-style tuba is heard on the Red Hot Peppers records. It’s often said that a great deal of the success of the Red Hot Peppers recordings lay in their many hours of rehearsal. I believe it’s also because Jelly Roll’s aim was to balance his written arrangements with the spontaneity at the heart of jazz. He planned the tunes as carefully as possible, but when the soloists took their solos he got out of the way and gave them compete freedom to express themselves. The result was delicate and definitely swinging. Jelly Roll maintained the balance between improvisation and orchestration, and between the band as a unit and the creativity of the individual musicians.”

Jelly Roll Morton. Photo courtesy of Rutgers Institute of Jazz Studies.

Cullum comments on the Peppers’ recording of Morton’s “Dead Man Blues:” “The real brilliance of this piece is Morton’s innovative combination of three elements. He combined the older style of collective improvisation with his clever arranging, and added the new emerging style of featured soloists. The concept of hot soloing was radically stimulated by Louis Armstrong’s playing on his Hot 5 recordings released by Okeh just a year before Jelly made his Red Hot Peppers’ releases. It’s interesting that Jelly Roll creates space for his soloists in the Peppers but often does not solo himself— as Louis Armstrong always did. Jelly was ‘playing’ his band and its soloists as if they were his instrument. Duke Ellington later applied the same approach to great effect.”

Jelly Roll Morton’s playfulness is highlighted on “Grandpa's Spells,” heard here in a two-piano rendition performed by Dick Hyman and John Sheridan.

Morton’s recording career began in 1923, three years before his first sessions with the Red Hot Peppers, when he recorded a series of piano solos for the Gennett label—an offshoot of the Starr Piano Company in Richmond, Indiana. When Harry Gennett and his sons discovered that the recording process used by the Victor Company was in the public domain, they decided the record business might become more profitable than selling pianos. Some of the most famous recordings in jazz history were made at the Gennett studio, a small wooden shed built behind the piano factory. Trains from nearby railroad tracks roared past the building, throwing many a recording stylus off its track.

King Oliver's Creole Jazz Band, 1923. Photo courtesy of the Frank Driggs Collection.

1923 was a notable year for jazz at Gennett. King Oliver’s Creole Jazz Band made its very first recordings there on April 6 in historic sessions, producing Oliver’s first recorded jazz masterpieces and also the first recorded solos of Oliver’s young cornetist Louis Armstrong. That same year, Jelly Roll Morton teamed up with the New Orleans Rhythm Kings at Gennett for the first openly, mixed-race session in recording history. The NORK were an inventive group of young white musicians from Chicago heavily influenced by Oliver. Morton’s “Milenberg Joys” is one of the classic titles from that ‘Jelly Roll-NORK’ session, and it’s performed here as Dick Hyman joins The Jim Cullum Jazz Band.

Shortly before the groundbreaking Red Hot Peppers sessions for Victor, Richard M. Jones, a talent scout and recording manager for the Okeh Record Company, had a revolutionary idea. He decided to put together a small group of musicians for the sole purpose of making records, to be fronted by a musician who would bring new status to Okeh’s “race record” market. Jones needed a fresh, new talent—a black artist with star power—to make it work.

"Heebie Jeebies" record label. Image in public domain.

In 1925 Louis Armstrong had been making waves in New York playing with the Fletcher Henderson Orchestra, and backing blues shouters Ma Rainey and Bessie Smith. But Louis’ wife Lil convinced him to move back home to Chicago where she had found steady work for him (and where she could keep an eye on him). A week after Armstrong returned to Chicago, Richard M. Jones ran into him at a free-lance recording date. Jones was inspired by Armstrong’s playing, and he pitched Okeh’s chief talent scout Tommy Rockwell on presenting Louis as the ‘world’s most exciting young cornetist’ in an all-star quintet, performing New Orleans-style jazz with New Orleans musicians. Armstrong recruited some of the best musicians from the Crescent City then working in Chicago. He lined up ‘tailgate trombone’ master Kid Ory, clarinetist Johnny Dodds and Johnny St. Cyr on banjo. After a few rehearsals at Armstrong’s flat, the group entered the Okeh recording studios in November of 1925. Most of the music was composed especially for the session.

From 1925 to 1928 the Hot 5, and later the Hot 7 with pianist Earl Hines, recorded some of the most influential and lasting examples of New Orleans jazz ever recorded. The Hot 5 performed publicly only one time, in 1926 at a benefit organized by the Okeh Company’s ‘race record’ department. The featured attraction at the benefit was Louis Armstrong and his Hot 5 re-creating the session that produced “Heebie Jeebies,” which has since taken its place in jazz history as the first recorded example of “scat” singing. It was also the Hot 5’s first commercial hit.

Young Louis Armstrong. Photo in public domain.

As Armstrong liked to tell it (and musicians liked to hear it), while the band was recording “Heebie Jeebies,” he unintentionally dropped his lyric sheet on the floor, forcing him to improvise the vocal. Lil Hardin Armstrong and Kid Ory later expressed their doubts about the ‘accidental’ loss of a lyric sheet, saying Louis had the whole thing planned from the start.

The players on the Hot 5 sessions had no idea these recordings would become classics of hot jazz. To the modest, young Armstrong, the Hot 5 experience was “a piece of cake.” “It was just a gig to us,” he said. Kid Ory took it a little further. “I think the reason those records came out so well was the folks at Okeh let us alone. You couldn’t go wrong with Louis.”

The tune “My Heart” composed by Lil Hardin Armstrong started out in 1920 as a waltz, but Armstrong and his band gave it a new ‘hot’ treatment at the first Hot 5 session for Okeh. On our interpretation heard here, Chicago tuba player Mike Walbridge and San Francisco cornetist Leon Oakley join The Jim Cullum Jazz Band. Other famous titles from the Hot 5 and 7 sessions performed on our radio show this week are “West End Blues” and “Potato Head Blues,” the latter includes an arrangement of the famous Armstrong solo written out and harmonized for three horns.

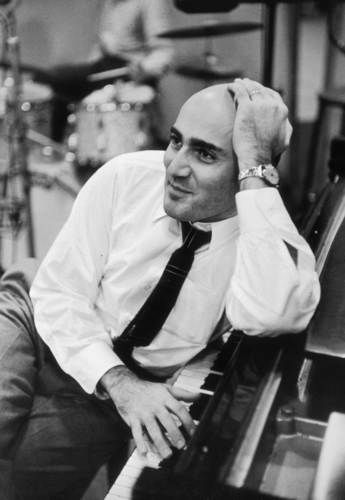

Russian-born jazz record producer George Avakian. Photo courtesy of Metronome.

Veteran producer George Avakian is a legend on the American music scene. He’s produced best-selling albums by Duke Ellington, Benny Goodman and Louis Armstrong, and he was the first producer to record a music festival—the Newport Jazz Festival in 1956. In 1940 Avakian, then a student at Yale University, managed to convince Colombia Records to reissue a collection of Armstrong’s Hot 5 and Hot 7 recordings. Many early jazz recordings were, by then, long out-of-print; the masters buried in vaults at recording companies. In spring 1940 Avakian changed that. The president of Colombia Records invited George to make himself at home in the company vaults. He was allowed to select out-of-print masters he thought worthy of reissue. Some of these masters had never been released. The first set of Colombia’s “Hot Jazz Classics” George Avakian produced was called King Louis. Soon to follow were definitive collections of the music of Bix Beiderbecke, Bessie Smith and Fletcher Henderson.

In a Riverwalk Jazz phone interview with George Avakian from his home in Riverdale, NY, he describes the process of discovering never-before-issued material in the Colombia vaults and comments about the enthusiasm of jazz recorded in the 1920s compared to present day recordings:

“The main thing is that there wasn’t any self-consciousness because there were no magazines, no publicity outlets to tell these musicians they were so great or anything like that, and there was no competition. Musicians were not voted on in polls and that sort of thing. What they played was just what they wanted to play. As a result, the basic enthusiasm the musicians had is preserved right there in the recording studio.”

Long after Bix Beiderbecke’s death, his friends would recall the cornetist’s utter lack of humor when it came to music. Maybe that’s why he kept it simple when he had to come up with a name for the six-man band he put together for a recording date in October 1927. No Hottentots, no Whoopie-Makers, just his pals from the Frankie Trumbauer Orchestra. He called his small recording group, Bix and His Gang. That session produced three sides, “At the Jazz Band Ball,” “Royal Garden Blues” and “Jazz Me Blues.”

;

;

"At The Jazz Band Ball" record label. Image in public domain.

At the start of that session, it didn’t look promising. The guys were tired, grouchy and a little hung over. At one point Bix and trombonist Bill Rank got into a scuffle in the middle of recording one of Bix’s solos. In spite of the tension, the recordings came off as relaxed, musically intelligent examples of small ensemble jazz. Bix’s solos have taken on legendary status, inspiring many. On this broadcast, The Jim Cullum Jazz Band performs two titles made by Bix Beiderbecke’s small recording groups, “Goose Pimples” and “I Need Some Pettin.'”

For music lovers who didn’t hear the great hot jazz bands of the 1920s in person, these small group recordings of the era offer a passport to another universe—just as Bix Beiderbecke was captivated listening to the Original Dixieland Jazz Band on a Victrola in the family parlor in Iowa. Or, how lives were changed in a Chicago soda shop as Jimmy McPartland and the rest of the Austin High Gang sat listening for hours to the New Orleans Rhythm Kings on a windup record player.

Jim Cullum recalls his own experience in the 1950s as a teenager in San Antonio working his way through his father’s collection of old 78-RPM recordings. Jim’s discovery of these small group hot jazz recordings led him to take up the cornet. His growing interest in the music led him to form the Happy Jazz Band and the Landing Jazz Club with his father in 1963. His life’s work, The Jim Cullum Jazz Band has now been performing for over half a century.

Photo credit for Home Page:Jelly Roll Morton's Red Hot Peppers. Photo courtesy of knowla.org.

Text based on Riverwalk Jazz script by Margaret Moos Pick ©1998