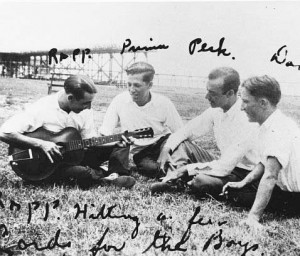

Peck Kelley band c. 1925 at Sylvan Beach, Galveston, TX. Peck is fifth from the left; Pee Wee Russell and Jack Teagarden are on his right. Photo: Jim Cullum collection.

Peck Kelley was a famously shy man and a virtuoso pianist with a gift for attracting the best and brightest young jazz players from around the country to his band in East Texas. Top bandleaders of the day tried to lure him away but he refused to migrate to fertile and more lucrative jazz scenes elsewhere. Instead he created a center for hot jazz in East Texas at a time when jazz was seldom heard anywhere other than New Orleans or Chicago.

All his life Peck Kelley lived in the same small house in Houston and had the same old battered piano. He got around town on the bus. But he could play piano, as one national reporter put it, "like an inspired archangel in the back room of a barbecue dive."

Peck Kelley was born John Dickson Kelley in 1898; one of nine brothers. There was an old upright piano in the parlor and Peck got his nickname because he was always 'pecking' at that piano. Early on Kelley was fascinated with the music of classical masters like Bach, Debussy and Chopin. A friend said that Peck's hands flew over the keyboard as he wove classical figures and runs into pop songs of the day. Around 1917 Peck discovered another kind of piano-playing. Six blocks from his home there was a 'red light district' where he learned boogie woogie and blues.

1924 New Orleans, from left: guitarist Leon Roppolo, Louis Prima, Peck Kelley, and Don (last name unknown). Photo from Dr. Edmond Souchon Collection, LSU Digital Museum, ponchetrain.net

Peck Kelley put together a jazz band in September of 1921, recruiting the best young musicians around, including a fresh-faced, 16-year-old trombonist—Jack Teagarden. Kelley called his band Peck's Bad Boys, and they played everything from fox trots and waltzes to pop songs, but it all came out sounding like jazz. They had steady work playing for frat parties, dinner dances and holiday events in Houston. Then in 1922 Peck's Bad Boys got their dream job—playing all summer long for nightly dances at the open-air Gardens of Tokio ballroom in Joyland Park on the beach on Galveston Bay.

Today Peck Kelley is an iconic figure among jazz musicians, but remains virtually unknown outside a small circle of aficionados. This week on Riverwalk Jazz, piano legend Dick Hyman joins The Jim Cullum Jazz Band to tell the story of Peck Kelley and revive the East Texas hot jazz of Peck’s Bad Boys.

"Rose of the Rio Grande," 1922 Sheet Music. Image from University of Colorado, Digital Sheet Music Collection

In spite of the fact that Peck Kelley never made any commercial recordings, there has been a 'Peck Kelley myth' among musicians—stories about a great but anonymous piano player down in Texas. Jack Teagarden held that Peck was the "greatest piano player in the world," and bandleader Ben Pollack remarked that, "a man would have to practice 36 hours a day to play music like Peck!"

The outside world first began to hear about Peck Kelley in a 1939 article in Down Beat titled, "Peck Kelley is No Myth," written by record producer John Hammond. In 1940 Collier's ran a sensational piece about Peck called "Kelley Won't Budge." All this national publicity made it harder than ever for Peck to live life on his terms. He stopped playing music in public performances. Peck Kelley told writer Dick Hadlock, "I like to play for myself. When I was on the stand playing in front of people, I was always wishing I could be doing the same thing at home instead."

This week's Riverwalk Jazz broadcast offers listeners an opportunity to listen to a rare recording of Peck Kelley's piano playing and hear Dick Hyman's comments on the real life piano playing of the Texas legend.

Photo credit for Home Page: Pianist Peck Kelley, 1943, Houston. Photo by Alfred Eisenstaedt, from blogs.houstonpress.

Text based on Riverwalk Jazz script by Margaret Moos Pick ©2009