Harold Arlen at 21. Photo courtesy of Sam Arlen.

This Riverwalk Jazz broadcast celebrates one of America’s least-known composers. Ironically, Harold Arlen’s compositions are among the most widely performed works in the American Popular Songbook. Piano master Dick Hyman and Australian songstress Nina Ferro join The Jim Cullum Jazz Band on stage at The Landing.

Born Hyman Arluck, the son of a Buffalo, New York cantor, he wanted to make it big as a vaudeville singer, not as a songwriter. As fate would have it, Harold Arlen’s catalog of published songs reads like an encyclopedia of America’s greatest hits. He wrote blockbuster numbers that became signature songs for a generation of stars. He gave Frank Sinatra “That Old Black Magic.” He created “Over the Rainbow” for Judy Garland. His “Stormy Weather” was a smash hit for both Ethel Waters and Lena Horne.

Tin Pan Alley photo courtesy tumblr.

Harold Arlen landed in New York City during the heyday of Tin Pan Alley in the 1920s, at a time when the Brill Building on 49th St. in Manhattan was a beehive of musical activity. It was a song factory where the halls echoed with the sound of a hundred pianos as composers and lyricists worked away in their cubbyhole offices, each trying to come up with the next big hit.

Jobbing around New York in 1925, Harold Arlen began to make a name for himself as a singer. He fit right into the hip, new singing style of the 1920s. His light voice and charming good looks made him a natural crooner, but he just couldn’t make a breakthrough to stardom as a singer. He had to pay the rent by working as a piano player. One day, he was subbing as a rehearsal pianist for Fletcher Henderson on a Broadway show, and Arlen’s noodling around on piano during a break caught the ear of the great African-American composer Will Marion Cook. Cook urged Arlen to come up with a song based on what he’d heard of his noodling around. The result was Arlen’s first major hit, the 1930 song, “Get Happy,” performed here by Dick Hyman and The Jim Cullum Jazz Band.

Frank Sinatra and Harold Arlen. Photo courtesy of Sam Arlen.

The opening night performance of “Get Happy” at the George M. Cohan Theater was notable for the hot jazz musicians in the pit band: Benny Goodman, Joe Venuti, Miff Mole and Red Nichols. All the high-powered talent couldn’t save the Nine-Fifteen Review which closed after only seven performances. Arlen’s “Get Happy” not only survived the shows’ demise, it became a radio hit on, widely covered by jazz bands nationwide. Arlen later told friends that the success of “Get Happy” made him realize he didn’t have the temperament to make it as a singer.

On this broadcast tribute to Harold Arlen, the piano duo of Dick Hyman and John Sheridan perform two of Arlen’s ‘novelty piano’ pieces, “Rhythmic Moments” from 1928 and “American Minuet” from 1942, both of which show the influence of Arlen’s close friend George Gershwin, and the impact of the ascendant jazz masters of the era, Louis Armstrong and Earl Hines. Dick Hyman says, “Arlen was a composer who wrote songs which have become standards for jazz players in particular, because he associated with the great black jazz players of the 1920s. He wrote scores for Cotton Club performers like Duke Ellington, Cab Calloway and Ethel Waters.”

Guest vocalist Nina Ferro talks about Arlen’s songs from the singer’s perspective: “There can be quite complicated patches that he’s written, but he’s done this on purpose to create a certain mood and feel which makes these songs stand the test of time.”

Lyricist Ted Koehler on left and Harold Arlen on right. Photo courtesy of Sam Arlen.

In 1932 Arlen teamed up with lyricist Ted Koehler to write a show called Vanities featuring a youthful Milton Berle. Arlen said the producer never paid either songwriter for any of the tunes they wrote for his shows, “not even a tie for Christmas.” Vanities produced the classic “I Gotta Right to Sing the Blues,” which later became the theme song of Texas trombonist Jack Teagarden.

Between 1930-34 Arlen did some of his most remarkable work composing scores for the lavish floor shows at Harlem’s Cotton Club, which reigned supreme as Manhattan’s premier nightclub. Lady Mountbatten called it “the aristocrat of Harlem.” Entertainment at the Cotton Club featured chorus lines of beaded and bangled dancers, orchestras led by Cab Calloway or Duke Ellington, or star attractions like Ethel Waters, Bill “Bojangles” Robinson and the tap-dancing Nicholas Brothers. Coast-to-coast live radio broadcasts from the club added to the glamour, and the clientele was as dazzling as the stage shows. Unlike some other Harlem nightclubs, every face in the audience was white and every face onstage was not. Bouncers at the door made sure there were no mixed parties at the tables. The Cotton Club’s gangland owners, Owney Madden and a shadowy character known as “Big Frenchie,” strictly enforced the policy.

Many of Arlen’s greatest songs, such as "Let's Fall in Love" and "Stormy Weather," were written with lyricist Ted Koehler for Cotton Club shows. On this broadcast, Nina Ferro interprets “Between the Devil and the Deep Blue Sea,” introduced in the 1931 Cotton Club revue Rhythm Mania.

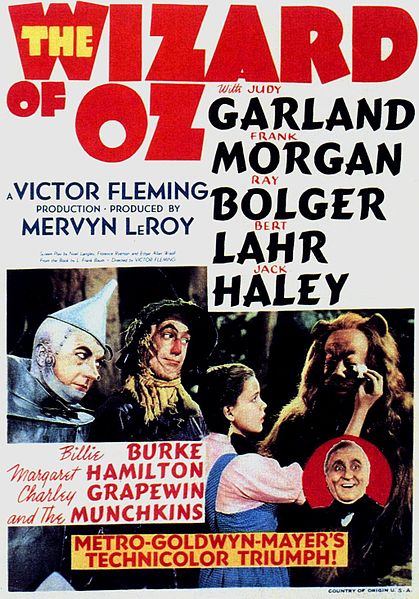

Wizard of Oz original poster, 1939. Image courtesy Wikimedia.

Throughout his career Arlen became friends and worked with some of the greatest lyricists of all time, particularly in his work on Hollywood film scores. His collaboration with Yip Harburg produced the score for the 1939 film The Wizard of Oz. Two tunes from the score are performed on this week’s show: “Ding! Dong! The Witch Is Dead,” performed by the full Band and “Somewhere Over the Rainbow,” presented by Dick Hyman in a spectacular solo piano rendition. Also in 1939, Arlen and Harburg wrote “Lydia the Tatooed Lady” for the Marx Brothers film At the Circus. John Sheridan and Dick Hyman have fun with this number on the broadcast.

One of Arlen’s most productive partnerships was with lyricist Johnny Mercer in the 1940s. Arlen composed many of his most famous standards such as “Ac-cent-tchu-ate the Positive," "Blues in the Night," "My Shining Hour" and "That Old Black Magic" with Mercer.

Harold Arlen and Johnny Mercer. Photo courtesy of Sam Arlen.

One night in 1945, Mercer showed up at Arlen’s house for a working session, only to find Arlen still locked in his study working on a melody. When Mercer heard Arlen’s tune for the very first time, he instantly came up with an idea for the opening lyric. He said, “It’s got to open with the line, ‘I’m gonna love you, like nobody’s loved you.’” Arlen, kidding around, said, “Come hell or high water!” Mercer shot back, “That’s close, but how about ‘come rain or come shine?’” Here, Nina Ferro joins the The Jim Cullum Jazz Band on the Arlen-Mercer classic, “Come Rain or Come Shine.”

Arlen created the score for the 1952 Judy Garland film A Star is Born with Ira Gershwin. In 1954, with Truman Capote he wrote the score to the Broadway production of House of Flowers in which Diahann Carroll introduced “A Sleepin' Bee,” a song which has since become a well-recorded jazz standard, and is performed on this broadcast by the Band with Dick Hyman. Arlen’s songwriting career continued on well into the 1970s. Unlike many of his peers from the ‘golden age’ of American Popular Song, Harold Arlen continued to write songs and be hugely successful through the onset of Rock and Roll and the British Invasion of The Beatles. Harold Arlen died in 1986 in New York.

Photo credit for Home Page: Harold Arlen. Photo courtesy songwriters1.org

Text based on Riverwalk Jazz script by Margaret Moos Pick ©1996