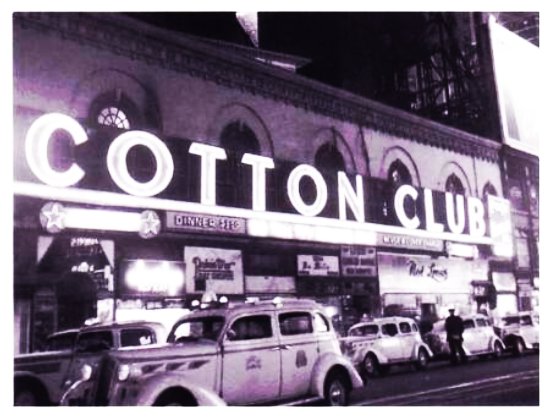

The Cotton Club,1936. Photo courtesy wikischolars.columbia.edu

On our show this week, The Jim Cullum Jazz Band and their guests toast the sensational entertainers and the cream of the crop of ‘golden age’ songwriters who made The Cotton Club sparkle in the 1920s and 30s. The building at the corner of Lenox Avenue and 142nd Street in Harlem had seen a few failures. It went belly up as a vaudeville theater and dance hall in 1918. In 1920 the nightspot was re-born as Club DeLuxe, a supper club run by heavyweight ‘boxing champ turned musician’ Jack Johnson. Operating out of his Sing Sing prison cell, mobster Owney Madden took over the nightclub in 1923 and christened it The Cotton Club. It would soon become an exclusive and exciting destination for wealthy downtowners fascinated by Harlem nightlife. With Prohibition in full force, a popular nightclub was a profitable outlet for Madden’s illegal booze—"Madden's Number One."

Every so often a slight, mild-mannered gentleman with China-blue eyes stepped down from his luxurious, bullet-proof Dusenberg saloon to inspect the premises of The Cotton Club, to make sure his orders were being followed to a T. Mr. Madden knew what he wanted and how he wanted it done, down to the finest details. He hired the most impressive black performing artists in New York City for his shows and signed Broadway’s top white songwriters to compose the scores for his dazzling revues. He positioned The Cotton Club to present first-class, authentic black entertainment to a wealthy, whites-only audience. He catered to Manhattan’s young ‘caviar and martini’ crowd, out looking for a buzz of illicit pleasure wrapped in safe and suitably elegant surroundings.

Cab Calloway on New Year's Eve at The Cotton Club,1937. Photo © Bettmann/CORBIS

Waiters dressed in red tuxedos looked convincingly like butlers, deftly popping champagne corks and serving exotic dishes from a midnight supper menu of Venison Steaks, Chinese Chop Suey and Toasted Sandwiches on call for clientele swathed in glitz and bling. Unlike staff at Small's Paradise a few blocks away, Cotton Club waiters did not dance ‘The Charleston’ on roller skates while serving at table. The Cotton Club was far too stylish and sophisticated for that kind of thing.

The vast nightclub was arranged in two concentric tiers of tables laid out in the shape of a horseshoe. Murals trimmed the walls around the room. In his autobiography Cab Calloway recalled, "The stage set looked like a 'Sleepy Time Down South' stage set from the days of slavery. The bandstand was a replica of a southern mansion with large, white columns and a backdrop painted with weeping willows and slave quarters. The band played on the veranda of the mansion. A few steps down was the dance floor, which was also used for floorshows."

The ‘plantation theme’ of the Cotton Club's decor played out for real in the club's strict segregation policy. Clientele and management were white, the entertainers and workers were African-American. Chorus girls had to be light complexioned, or as the advertising promised—"Tall, Tan and Terrific"! The Cotton Club opened for business at 9:00 o’clock in the evening with music for dining and dancing. Just after midnight, the first floorshow kicked off and the final elaborately staged song and dance revue ended at 3:00am before dawn could break the spell.

Duke Ellington. Photo is free use

The Duke Ellington Orchestra opened as house band at The Cotton Club in 1927. The handsome young bandleader perfectly turned out in top hat and tails was about to make a name for himself at the hottest, classiest club in Harlem. Live radio broadcasts from the club fanned the flames of Ellington’s star power. Constantly faced with tight production deadlines, Duke Ellington wrote music fast and under great pressure. Even so, he developed a trademark style pleasing to his mobster bosses and dazzling the club’s upscale patrons. Ellington compositions written in the late 1920s and performed here by The Jim Cullum Jazz Band, such as “Black and Tan Fantasy,” and “Creole Love Call,” remain exciting and compelling music today.

In the late 1920s and early 30s The Cotton Club was the best venue in the country to introduce a new song. Word of mouth and network radio broadcasts from the club had the power to launch a hit tune overnight. In 1927 Hoagy Carmichael wrote his most ambitious song but the tune went nowhere. In 1928 Mitchell Parrish added a lyric. Still nothing happened. In 1929 Duke Ellington introduced it at The Cotton Club, and Hoagy's “Star Dust” took off. This week we hear “Star Dust” in an instrumental feature for trumpeter Nicholas Payton with The Jim Cullum Jazz Band.

Mob boss Owney Madden demanded and got the best talent in Manhattan to write, produce and perform in The Cotton Club's lavish stage productions. Top Broadway and Tin Pan Alley songwriters, including Irving Berlin, Fields and McHugh, and Arlen and Koehler wrote a string of hit tunes for The Cotton Club.

Jimmy McHugh and Dorothy Fields. Photo by Peter Mintum Co.

It was 1927; the same year Duke Ellington made his Cotton Club debut that the 23-year-old, fledgling lyricist Dorothy Fields began collaborating with composer Jimmy McHugh on songs for Cotton Club floorshows. Together Fields and McHugh captured the attitude of the times in their songs—McHugh with his swinging rhythms and Fields in the teasing slang of her lyrics. Much of their work, jazzy numbers like "Freeze and Melt" and "Diga Diga Doo," were closely associated with Duke Ellington's Cotton Club Orchestra, but the Fields and McHugh team also produced hit pop songs, like the Depression-era anthem "I Can't Give You Anything But Love."

A completely new floorshow was mounted at The Cotton Club every six months, and producer Dan Healy insisted the pacing of the floorshows be fast and furious. Dance routines were wild. Spotlights played over chorus girls dressed in a few strategically placed feathers and spangles. Elaborate stage sets and intricate lighting, combined with an ever-changing, star-studded cast, put Cotton Club revues on a par with anything on Broadway at the time. Glamorous blues singers Ethel Waters and Lena Horne and the exotic dancer Josephine Baker made The Cotton Club sizzle. Vaudeville great Bill "Bogangles" Robinson and the acrobatic tap-dancing Nicholas Brothers brought a taste of the Big Top to Cotton Club stage shows.

On this edition of Riverwalk Jazz, tap sensation Savion Glover remembers Bojangles as he dances his way through a live crossfade from Jimmy McHugh and Dorothy Fields’ 1928 tune composed for Robinson at The Cotton Club, "Doin' the New Low Down."

Nicholas Brothers. Photo courtesy Wikipedia.

The story goes that Jimmy McHugh was responsible for bringing Duke Ellington to The Cotton Club in late 1927. When the Club needed a new house band, the management first invited King Oliver and his Dixie Syncopaters to take over. But Oliver turned down the gig; he felt he wasn’t offered enough money. It proved to be the biggest mistake of his career. Jimmy McHugh stepped in and recommended a band he'd heard at the Kentucky Club in Times Square, called The Washingtonians. Cotton Club management wasn't keen on hiring a "non-Chicago" band. Owney Madden had a strict policy of hiring everyone from busboys to bandleaders through his Chicago mob connections. McHugh kept pitching. He felt strongly that this band from Washington DC, led by a stylish, young pianist named Ellington, would be just right for The Cotton Club. McHugh arranged an audition for Ellington, and his band got the job. One problem remained—Ellington had a contract for a long-running engagement in Philadelphia. Madden sent his most persuasive goons to Philly to discuss the problem with the manager. Of course, the nightclub manager relented. Duke Ellington and his men arrived at The Cotton Club opening night minutes before show time, on December 4, 1927.

Live national radio broadcasts from The Cotton Club on both the CBS and NBC networks were enormously popular. Anyone with a radio anywhere in America could tune in to the sophisticated sounds of The Duke Ellington Cotton Club Orchestra broadcasting live for dancing from the fabled nightspot, a hip meeting place where celebrity guests from movie stars Mae West and Judy Garland to playwright Moss Hart and poet Langston Hughes rubbed shoulders with composer George Gershwin and New York City Mayor Jimmy Walker. The wealthiest New Yorkers mingled with the shadiest characters in the city’s underworld.

Harold Arlen and Ted Koehler. Photo courtesy Sam Arlen.

In 1930 songwriters Harold Arlen and Ted Koehler took over for Dorothy Fields and Jimmy McHugh as The Cotton Club's in-house songwriting team. Less than a year before he snagged his job at The Cotton Club, Arlen had been trying to make a career for himself as a jazz singer, not a songwriter. Arlen changed his mind about his career path after stumbling into a successful collaboration with lyricist Ted Koehler on the very first song he composed, "Get Happy." In the spring of 1930, "Get Happy" (performed here by The Jim Cullum Jazz Band) was introduced at the Silver Slipper, another nightclub run by Owney Madden. The success of “Get Happy” bought Arlen and Koehler their ticket to a gig as The Cotton Club’s resident songwriters. Fifty dollars a week, plus all the food they could eat, wasn't much of a paycheck in New York in the 30s but the Cotton Club job gave the aspiring songwriters an opportunity to work with star-studded casts, and the prospect of being heard by all the right people. In 1931 the Arlen/Koehler songwriting team introduced "Between the Devil and the Deep Blue Sea" into the Cotton Club revue Rhythm-mania where it became a hit for singer Ada Ward. Here, London-based vocalist Nina Ferro takes center stage with The Jim Cullum Jazz Band to offer her interpretation of this classic jazz standard by the Arlen/Koehler team.

Ethel Waters. Photo © William Gottlieb, courtesy Wikimedia.

Of the many enduring Cotton Club hits by Arlen and Koehler, "Stormy Weather" is a perennial favorite. Introduced in 1933 by Ethel Waters in The Cotton Club's 22nd revue, mounted to celebrate Duke Ellington's much-anticipated return from a movie-making jaunt in Hollywood. The set for “Stormy Weather” was simple—a cabin, a lamppost and Ethel Waters bathed in a deep blue spotlight. Lighting cues flashed and sound effects created the rumble of a thunderstorm as Waters sang the blues. A dozen encores later, Ethel Waters and "Stormy Weather" were the talk of New York. A beautiful young chorus girl in the show at the Cotton Club bided her time. Lena Horne would go on to do it her way in a memorable scene in the 1943 movie Stormy Weather.

The Cotton Club bosses were in a jam when Duke Ellington and his Orchestra left for Hollywood to make the Amos 'n Andy movie Check and Double-Check in 1930. Where could they get a replacement to match the popularity of Ellington? They turned to a virtually unknown, youthful showman with a mighty voice, a former law student and drummer, Cab Calloway. Mr. Hi-De-Ho.

Cab Calloway, 1937. Photo in public domain.

The story goes that Calloway was fronting a band called The Missourians in a downtown nightspot when four men in wide-brimmed hats showed up and suggested that Cab make a point to be at The Cotton Club for rehearsal the next day. Calloway kept the appointment and stayed for years. Trumpeter and Riverwalk Jazz favorite Doc Cheatham spent years on the bandstand with Cab Calloway at The Cotton Club, and on the road coast to coast. Here, Doc joins The Jim Culllum Jazz Band in a 1990 recording session captured live at The Landing and sings, "I've Got the World on a String,” a number Cheatham often played with Cab's band at The Cotton Club.

Cab Calloway was all show biz on the bandstand. In this pre-rock and roll era, no one would dream of carrying on like Cab did. He waved his arms, strutted back and forth across the stage, and his hair fell in his face as he leapt into the air. Cotton Club customers fell in love with his zany antics, but Calloway was also a savvy bandleader; he drew some of the best jazz musicians of the day into his band. Bass legend Milt Hinton worked with Cab Calloway at The Cotton Club for years, and in 1939 while with Cab, Hinton wrote "Pluckin' the Bass.” Here, Milt joins The Jim Cullum Jazz Band on stage at The Landing to perform his original classic, “Pluckin’ The Bass.”

The Cotton Club in Harlem closed in 1936 only to re-open in Times Square soon after, boasting headliners Cab Calloway, The Singing Dandridge Sisters, The Dancing Nicholas Brothers and even Louis Armstrong's band. The Times Square location lasted less than four years. The Cotton Club closed its doors for the final time in 1940. Tastes in entertainment had changed. Younger audiences were taken up with the new sound of the Benny Goodman and Artie Shaw swing orchestras. The thrill of the forbidden faded with the repeal of Prohibition, and Harlem wasn't such a mystery to the Manhattan crowd anymore.

Pianist Dick Hyman and actor Vernel Bagneris join The Jim Cullum Jazz Band for "Drop Me Off in Harlem," Duke Ellington's 1933 homage to the "classy uptown" place where you could always find "the best party in town."

Photo credit for Home Page: Cab Calloway, 1937. Photo in public domain.

Text based on Riverwalk Jazz script by Margaret Moos Pick © 1997