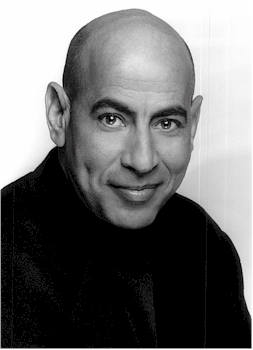

Vernel Bagneris. Photo courtesy of the artist.

Talking about his life in post-Katrina New Orleans, actor and playwright Vernel Bagneris says, “I need New Orleans. New Orleans is me. It’s my culture. It’s my way of being. I get along wherever I go, but I really feel like I’m wearing my own skin when I’m in New Orleans.”

This week on Riverwalk Jazz, Vernel Bagneris talks about growing up in the New Orleans Creole community in the 1950s and 60s, and what it is like to live there now.

New Orleans jazz is as rich and varied as the city itself, borrowing melodies and rhythms from Spanish, French, Creole and African culture. When we spoke with Vernel in 2006, redevelopment was inching forward and everyone wondered what the city's next incarnation would be. On this broadcast The Jim Cullum Jazz Band revives the music of early 20th century New Orleans. Offering a program of music that includes the Maceo Pinkard composition “Storyville Blues,” Topsy Chapman takes the vocals on another Pinkard classic, “Darktown Strutters Ball.” Also on the bill, the title track “New Orleans Stomp” by King Oliver. And, “The Pearls” by Jelly Roll Morton, the piano legend who grew up in the same 7th Ward Creole neighborhood as Vernel Bagneris—but a hundred years or so earlier.

Piron's New Orleans Orchestra, 1924. Photo courtesy jazzagebanjo.wordpress.

Bagneris comes from a New Orleans Creole family steeped in jazz history. One of his great uncles was the New Orleans violinist, composer and bandleader of the 1920s, Armand J. Piron. Another great uncle, Joe Loomis, was a popular vaudeville performer on the TOBA circuit.

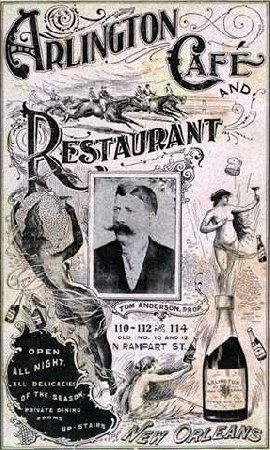

Poster for the Arlington Cafe, opened in 1892 by Tom Anderson, unofficial mayor of Storyville. Public domain.

Vernel's love for the unique heritage of earlier jazz forms came as a natural outgrowth of his exposure, as a young man working on Bourbon Street, to traditional bands he heard in the French Quarter. Music was the natural fabric of life in New Orleans. Vernel remarks, “To me, I wasn’t listening to jazz. I was listening to New Orleans musicians play New Orleans music. It was all a very natural flow versus studying a musical style.”

Working in New Orleans in the 1970s, Bagneris created a theatrical revue celebrating the glory days of 1920s black vaudeville called One Mo' Time. He said, “We started working on the show in my living room. My musical director Orange Kellin lived next door and he’d have the band in his apartment. And I had the singers in mine. I’d work on the book in my apartment and give the actors their lines, then send them over to Orange for their harmonies, or whatever. It was just one of those neighborhood things— ‘everybody is going to get together tomorrow at six.’ They showed up on time, and they showed up for free. We practiced out of love and diligence.”

One Mo’ Time was to have played for one night only at the Toulouse Theater in New Orleans, but instead wound up a smash hit with a long run at the Village Gate in New York and on London's West End throughout the 1980s. One Mo' Time helped spark a revival of interest in New Orleans jazz. Vernel Bagneris notes, “In the 60s we went through a thing, the African American community in New Orleans and around the country, of putting down a lot of historic things. Tap dance was very out of favor. Jazz music was out of favor. As we got past anger into understanding …we reclaimed a very precious side of black entertainment.”

Photo credit for Home Page: Brass band in New Orleans. Photo in public domain.

Text based on Riverwalk Jazz script by Margaret Moos Pick ©2007