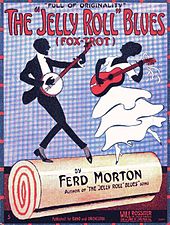

On this edition of Riverwalk Jazz, we re-visit early 20th century New Orleans to meet the man who claimed to be the inventor of jazz. Jelly Roll Morton was so expert at telling tall tales about himself, his inventions have sometimes been reported as fact. Whatever the myth, Morton’s true legacy is the high standard he set for the classic New Orleans jazz band; and his remarkable compositions—a book of complex and highly entertaining tunes that continue to be played and recorded to the present day.

His life was the stuff of legend. Depending on the whims of fate and fortune, Jelly Roll made his living as a pimp, a gambler, a fight promoter, a nightclub manager, a pool shark, a door-to-door patent medicine hawker, a bellhop, a tailor, and even a sharpshooter in a Wild West show. Jelly Roll Morton made hustling a fine art. When Lady Luck happened to smile his way, he sported a diamond gleaming in his front tooth, the finest threads on his back and a crisp thousand dollar bill in his pocket. He carried a pair of pearl-handled pistols to complete his outfit.

Morton billed himself as “the originator of jazz, stomps and blues,” and perhaps there was some truth to it. The recordings he made with his Red Hot Peppers in mid-1920s Chicago were groundbreaking works of genius and deeply influenced the course of New Orleans-style jazz. In this body of work, Jelly Roll Morton proved himself to be a magnificent musician, and a superb bandleader and record producer.

Jelly Roll and The Red Hot Peppers, Victor Church Studio. Photo in public domain.

The Red Hot Peppers recordings are a spectacular document of New Orleans jazz. “There’s nothing quite like it anywhere else,” says Jim Cullum. “The tunes and arrangements were all originals by Jelly Roll, meticulously created for the sessions. He hand-picked the top musicians on the scene and thoroughly rehearsed each number until he was satisfied. In those early days of the recording industry, this was a very unusual—recording companies didn’t give bandleaders the time and money for polished arrangements and paid rehearsals.

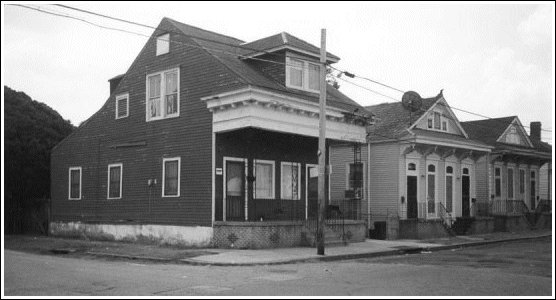

Jelly Roll's childhood home at 1443 Frenchmen Street, New Orleans. Photo in public domain.

Born about 1890 on the Gulf Coast near New Orleans, Jelly Roll Morton’s given name was Ferdinand Joseph LaMenthe. Morton said his forbears were in New Orleans long before the Louisiana Purchase and came to the New World directly from the shores of France. His ancestors, the Péchés and the Monettes, were among the city’s genteel “creoles of color” and spoke both French and Spanish, valued education, and attended the French Opera House. Morton identified what he called the “Spanish tinge” in the Tango rhythm in his compositions.

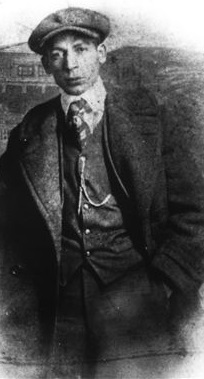

Young Jelly Roll Morton. Photo in public domain.

Jelly Roll was christened Ferdinand after the king of Spain but early on dropped LaMenthe in favor of his stepfather’s name Mouton, which soon morphed into Morton; he said the name change was for “business reasons.” His father—a handsome Creole with a wild streak a mile wide disappeared from his son’s life when Ferdie was a boy. Young Ferdinand was barely 14 years old when his mother died. Along with his two sisters, he went to live with his great-grandmother Mimi Péché. This arrangement didn’t go well nor did it last long. On the sly, Jelly Roll had been spending his afternoons developing a reputation as one of the top young piano players in New Orleans’ tenderloin district. Grandma Péché didn’t think music was a suitable career for any family member, let alone playing piano in Storyville bordellos.

One morning on her way home from Mass, she ran into Jelly Roll wending his way back after a night working as a piano “professor” in a brothel. She saw his fancy clothes and knew in a flash what he’d been up to. For Mimi Péché, musicians were bums and scalawags. She wasn't about to let Jelly Roll live in the same house with his innocent young sisters, and coldly shut him out of the family home. He was 15-years-old and out on the street on his own. For the rest of his life, whether riding high or hard up for cash, without fail Jelly sent money home to his grandmother and the sisters he loved but hardly knew.

Morton wound up spending most of his life on the road. After his grandmother threw him out, he took the train to Biloxi and stayed with his godmother Eulalie Echo (Hecaud). On the Gulf Coast, Creoles often practiced Catholicism and voodoo with equal fervor, and Eulalie was thought to be a voodoo queen. Jelly said he was frightened to see his godmother hold séances and cast spells. He considered himself a devout Catholic and not a believer in voodoo, but late in life he blamed his poor health on his godmother’s witchcraft.

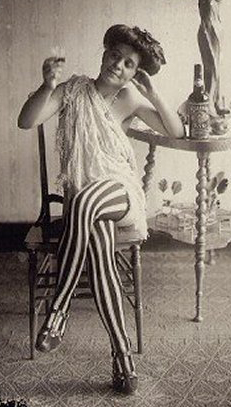

Storyville prostitute, 1920s. Photo in public domain.

Back on the road, in Mississippi Jelly Roll Morton was arrested for holding up a mail train. It was all a big mistake, or so the story goes, but Jelly did time on a chain gang until he could escape. Between 1910 and 1925, honky tonks and roadhouses were home for Jelly Roll Morton, and he spent most of his time playing piano, shooting pool, gambling and running a string of prostitutes in nightspots from San Francisco to New York City.

The high point in Jelly Roll Morton’s musical career came in the 1920s with the recordings he made with the Red Hot Peppers for the Victor label in Chicago. Many tunes on this radio show came from the Red Hot Peppers sessions. Jim Cullum says that Jelly Roll may not have invented jazz as he claimed, but he was “one of the first and one of the best. He comes across not only as a great piano man, but also as a terrific bandleader and composer. Morton had a deep understanding of how ensemble music ought to be played. It’s interesting that these Victor recordings have the added fun of sound effects and scripted skits leading into the tunes. It gives them a unique quality of fun, for example the spoken introduction to “Sidewalk Blues.””

"The Jelly Roll Blues" sheet music. Photo in public domain.

Bandleader Cullum goes on to say that Jelly Roll instinctively understood the need for musical dynamics in jazz performance. Morton made this astute remark about a music that was often performed in a raucous style, he said “Jazz music is to be played sweet, soft, plenty rhythm. When you have your plenty rhythm, with plenty swing, it becomes beautiful. To start with, you can’t make crescendos and diminuendos when one is playing triple forte. You’ve got to be able to come down in order to go up. If a glass of water is full, you can’t fill it anymore, but if you have a half a glass, you have an opportunity to put more water in it. And jazz music is based on the same principles.”

Down on his luck, toward the end of his life in 1938, Morton heard a broadcast of Robert Ripley’s radio show Believe It or Not that set him off on a tirade. On the broadcast, W.C. Handy was credited as the inventor of jazz and blues. Jelly Roll couldn’t believe his ears. He wrote a scathing letter to Down Beat magazine saying, “It is evidently known beyond contradiction that New Orleans is the cradle of jazz and that I myself happened to be the creator in the year 1902. Speaking of jazz music, any time it is mentioned, musicians hate to give credit, but they will say, ‘I heard Jelly Roll play it first.’”

Jelly Roll with two visitors at the RCA Manufacturing Co. studio #3 NYC, 1939, during his second Bluebird recording session. Photo © Ate van Delden Collection.

Not long after recording the Red Hot Peppers sides in Chicago, Morton moved to New York where he found his music suddenly out of fashion. His favored ensemble style had given way to star soloists. Louis Armstrong, Coleman Hawkins and Benny Goodman were the hot musicians in town. In 1935 Jelly Roll moved on to Washington D.C. where he ran a seedy little dive. He’d tend bar, seat people and play piano. His smile revealed that the diamond he had worn so proudly in his front tooth was at the local pawnbroker. Five years later in 1940 his godmother, the infamous Eulalie Echo, died in California. Jelly Roll felt he was under her spell as he set off on a wild trip to California to claim her diamonds. Packing everything he owned into his two remaining prized possessions, a Lincoln touring car and a Cadillac he headed west, towing the Cadillac behind the Lincoln. Even before he left town, he was feeling ill, and the trip turned into a nightmare. Caught in snowstorms, trapped on a mountaintop and sliding off the road into a ditch, he abandoned the Cadillac in Idaho. At last he reached Los Angeles, but his health took a turn for the worse, and Morton died on July 10, 1941.

More about the music, performed here by The Jim Cullum Jazz Band.

In 1918 Morton published his first tune. He was out in California, living the high life, driving a big car and the money was rolling in. He was playing at the Cadillac Café at the Newport Bar but made most of his folding money from his sidelines of gambling and prostitution. There are a number of stories about how his first published tune “Froggy Moore Rag” got its name. One story has it that Morton lifted the opening chords of the tune from a Cincinnati piano player by the name of Benson “Frog Eye” Moore. Jelly Roll claimed the tune came from his vaudeville days, explaining that he used this piece to accompany a contortionist who performed in a frog costume and billed himself as “Moore, The Frogman.”

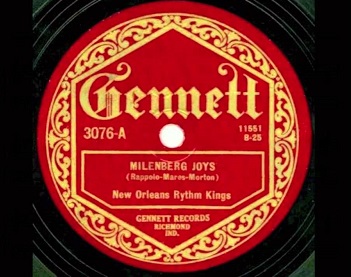

Milenberg Joys label. Image in public domain.

"Milenberg Joys" refers to a resort area on Lake Pontchartrain near New Orleans, called Milneberg. In 1923 the New Orleans Rhythm Kings recorded the tune with a band including Paul Mares, George Brunies, Jelly Roll Morton, and Leon Rappolo. “Milenberg” was the common New Orleans pronunciation for Milneburg and when the record came out the printed label reflected the common pronunciation rather than the correct place name. Although given credit for the composition, Jelly Roll Morton claimed to have written only the introduction.

Morton wrote “Kansas City Stomp” in 1919. Jelly explained, “The ‘Kansas City Stomp’ didn’t come from Kansas City. I wrote the tune down on the border of Mexico at a little place called Tijuana. The tune was named after a saloon run by a friend of mine by the name of Jack Jones. He asked me to name a tune after his saloon which was named the Kansas City bar, so I named it the ‘Kansas City Stomp.’”

"Burnin' The Iceberg" and "Tank Town Bump" were titles Jelly recorded for Victor in New York in 1929. “Tank Town” was one of many nicknames for New Orleans.

"Black Bottom Stomp" is based on one of the legendary 1926 Red Hot Peppers recordings Morton made in Chicago for Victor.

"Sweet Substitute" is Jelly Roll’s tribute to his days as a pimp. The “substitute” of the title and lyric is a polite redirection of “prostitute.”

"Wild Man Blues" was a 1927 collaboration between Jelly Roll Morton and Louis Armstrong that depended heavily on Armstrong’s virtuosic improvisation captured on the Victor disc.

"Freakish" existed only as a piano solo before John Sheridan wrote the arrangement heard this week expressly for the seven-piece Jim Cullum Jazz Band.

"Fingerbuster" is a virtuoso piano solo that Jelly Roll often used to “hustle” other pianists in informal competitions or “cutting contests.”

"Winin' Boy Blues" is another paean to Jelly’s youthful career as a piano professor in New Orleans Storyville brothels.

Photo credit for Home page: Jelly Roll Morton photo in public domain.

Text based on Riverwalk Jazz script by Margaret Moos Pick ©1992