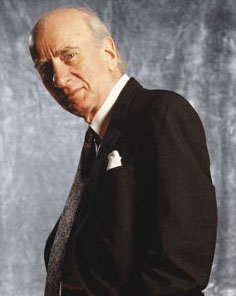

Dick Hyman photo courtesy of the artist

On this edition of Riverwalk Jazz, piano master Dick Hyman joins The Jim Cullum Jazz Band to explore the musical legacy of Earl Hines, arguably the most influential jazz pianist of the late 1920s and 30s.

In the early 1900s, pianos functioned as “one-man-bands,” and performances were in ragtime and later stride piano styles. The left-hand provided the bass and middle accompanying parts while the right played the melody. A solo piano performance in this “orchestral” style is self-sufficient.

Earl Hines was one of the first pianists to do more than simply supply rhythm to the jazz ensemble. The simplified style Hines developed supported and complemented the other rhythm instruments. But his soloing was revolutionary. He created a technique of playing a melody in octaves, often called the “trumpet” style of soloing, which allowed for “linear” improvisation on piano similar to a horn player. Many consider Hines to be the “father” of modern jazz piano playing.

Earl Hines was born in 1905 in Duquesne, Pennsylvania, a suburb of Pittsburg. As a boy, he loved to watch the magnificent draft horses used to pull beer wagons for local breweries. When Hines was young, he watched his stepmother play the family’s parlor organ, and imitate her by putting paper on a chair and pretending to play along. His father noticed, and realizing his son was interested in music, soon brought a piano into the house and found a teacher for him. Earl Hines loved music and studied hard. His cousin Pat Patterson discovered that Earl could play piano by ear, and loved having him around to play popular songs of the day. The story goes that when his cousin Pat went out with the ladies, he’d take Earl along to entertain them. Everywhere they went there was a piano, and Earl would play and the girls would gather around. Cousin Pat told his girlfriends, “To keep Earl playing, just give him a little hug and a kiss.” That’s what they did, and Earl played all night long without a clue as to what was going on until years later.

A key figure in the history of jazz, Earl Hines collaborated with Louis Armstrong on the Hot Five and Hot Seven sessions of the late 1920s, contributing to recordings that are among the most important in the genre. Tunes featured on this show from these classic recordings are: "Weather Bird," “Beaukoo Jack” and “Hear Me Talkin’ to Ya.” From 1928 into the 30s, Hines recorded a series of widely influential piano solos, among them "A Monday Date," "Cavernism," and "Fifty Seven Varieties," performed here by the piano duo of John Sheridan and Dick Hyman.

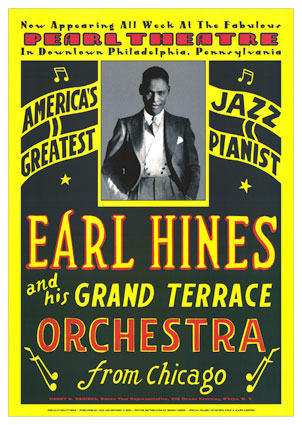

Earl Hines 1929 poster permission by The Big Bands Database at nfo.net

In 1928 Hines and his orchestra opened at Chicago's Grand Terrace Cafe. For many years, the Hines big band broadcast live from the Grand Terrace, garnering a huge nationwide audience. Many future piano greats later said their education in jazz came from listening to these broadcasts, among them Nat Cole, Jay McShann, Teddy Wilson and Art Tatum.

“Rosetta” was Earl Hines’ signature tune written in 1932 with his arranger Henry Wood. He played the tune thousands of times and sometimes would play it two or three times a night adapting it to every style imaginable. On our show, Jim Cullum tells this story: Hines and Wood were working together in Kansas City and every time Hines needed Wood, he’d be off somewhere with his girlfriend Rosetta. So Hines told Wood to bring Rosetta along, and he’d personally pay for whatever she wanted to eat or drink while they worked. It was the only way Hines could be sure that Wood would show up for the gig. The tune “Rosetta” began as a little impromptu piece Hines played on the job. When Wood heard it, they worked it up and couldn’t help but name it after Wood’s girlfriend— “Rosetta.”

Hines led his big band for 20 years, right up to the demise of big swing bands in the postwar period. During the WWII years, the Hines band was a hotbed of experimentation and new directions in jazz. Both Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie worked with Hines, as did Benny Carter, Wardell Gray and Gene Ammons. Hines’ featured singers were Billy Eckstein and Sara Vaughan. And Budd Johnson updated Hines' arrangements to reflect the new musical vocabulary of Parker and Gillespie.

Hines’ "bebop" band never recorded due to wartime materials shortages and recording bans. But we have the testimony of many who heard it. Charlie Parker's biographer wrote:

"...The Earl Hines Orchestra of 1942 had been infiltrated by the jazz revolutionaries. Each section had its cell of insurgents. The band’s sonority bristled with flatted fifths, off triplets and other material of the new sound scheme. Fellow bandleaders of a more conservative bent warned Hines that he had recruited much too well and was sitting on a powder keg."

By the 1950s Hines returned to work with Louis Armstrong on his All-Stars band. Eventually Hines settled in the Bay Area, forming his own Dixieland band. In 1971 Hines recorded a series of piano solos for the Audiophile label (My Tribute to Louis), at that time owned by Jim Cullum and his father. The "direct-to-disc" LPs were engineered by the pioneering recordist Ewing Nunn. The three-LP set features eight songs associated with Armstrong, including "Struttin' with Some Barbeque," "A Kiss to Build a Dream On," "Someday You'll Be Sorry" and two versions of Armstrong's theme "When It's Sleepy Time Down South."

A few years before his passing in 1983, Earl Hines appeared in San Antonio for an all-star "World Series of Jazz" concert organized by Jim Cullum. The concert band consisted of pianist Earl Hines, bassist Bob Haggart, drummer Ray Bauduc and jazz violinist Joe Venuti.

Photo credit for Home Image: Earl Hines 1929 poster permission by The Big Bands Database at nfo.net.

Text based on Riverwalk Jazz script by Margaret Moos Pick ©1990