With Ray Bauduc, Norma and Jack Teagarden, 1954. Photo courtesy Just Four Bars: The Life and Music of Kenny Davern, by Edward Meyers.

Kenny Davern was a kid when he first heard Pee Wee Russell play “Memphis Blues” and he knew then that he wanted a life in jazz. Over five decades his world-class playing on clarinet and soprano sax wowed the most discriminating fans. Even so, the spotlight that shone on him was never really bright enough. When we asked writer Nat Hentoff what he heard in Kenny’s playing, he said, "Kenny had this extraordinary presence, vitality and a continuous imagination. And he’s never gotten the full credit he deserves..."

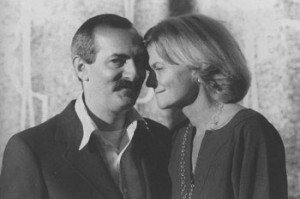

Kenny and wife Elsa, 1980. Photo courtesy Just Four Bars: The Life and Music of Kenny Davern, by Edward Meyers, Scarecrow Press.

One evening shortly before Christmas in December 2006, Kenny Davern was home in Santa Fe with his wife Elsa. He had been feeling lousy all day but didn’t want to make a fuss and get medical attention. Standing by the fireplace, he looked over at Elsa and said just two words, the same words he spoke the first time he saw her decades earlier, “Oh boy," he said. They would be his last.

Back in 1989, when we launched Riverwalk Jazz, Kenny Davern was the first musician we called to join us to be our guest. This week we’ll hear never-before-broadcast tracks from that pilot session as we honor this great artist.

Kenny Davern turned heads and galvanized audiences around the world for over fifty years with his instantly recognizable clarinet sound, his riveting solos and jewel-like tone. Kenny believed in telling the truth with his music. When he was on our bandstand, we knew it would be a 24-karat day.

In spite of playing an instrument that was almost totally out of fashion by the 1970s, Kenny was no stranger to accolades. The New York Times called him “the finest clarinetist playing today.” Piano legend Earl Hines upped the ante when he described Kenny as “the best jazz clarinetist since Jimmy Noone.” Bandleader Jim Cullum says, "There was no one like him in the history of jazz music. Kenny was unique both musically and as a man."

Davern was born in 1935 on Long Island, NY and raised by his maternal grandmother in Queens. Explaining what it was like when he happened to hear clarinetist Pee Wee Russell on the radio for the first time at the age of 11, Kenny said, "I heard this thing and whack! It was like being hit between the eyes with a baseball bat...it was a true emotional experience in jazz, and I remember it like it was yesterday. The music grabbed me and I listened to every thing I could.”

Early gigs with trumpeter Henry "Red" Allen led Kenny to his first big break at the age of eighteen when he won the baritone sax chair in the popular Ralph Flanagan big band. A year later he was invited to audition for trombone legend Jack Teagarden. Kenny recalled that day. After playing a few tunes with the band, Kenny said, "I saw Jack and his wife Addie up in the bleachers, talking during a break. So I walked over there. And I said, 'Well, what’s going on Jack?' He says, 'What do you mean, Kenny?' I said, 'Well, am I hired?' 'Of course you’re hired.' He said, 'Where’ve you been all my life?'”

At Central Plaza with Henry Red Allen, 1961. Courtesy Just Four Bars: The Life and Music of Kenny Davern.

The advent of the rock and roll revolution in the 1960s had a negative effect on Kenny's career. Just about the time Davern made a name for himself in jazz, the scene in New York began to cool. He found gigs around town with Buck Clayton, Red Allen, Bud Freeman and others, but audiences for jazz continued to dwindle. Davern recalls, “I could go to the Metropole …and on the bandstand there would be all the great players—Coleman Hawkins, Roy Eldridge. There was an awful lot going on musically, but not very much in terms of an audience.”

Beginning in the mid-60s, weekend "jazz parties" began popping up all over the United States, Europe, and Australia, revitalizing the careers of many jazzmen. One of the most memorable groups to come out of that scene was an ensemble Kenny Davern launched with reedman Bob Wilber in 1973. They both set aside their clarinets to play soprano sax in a group known as Soprano Summit. Together they recorded a dozen widely-acclaimed albums, and toured the U.S. and Europe. Other members of the group included Dick Hyman, Milt Hinton, Bucky Pizzarelli and Bobby Rosengarden. Over time Davern appeared on-screen in major motion pictures including The Hustler with Paul Newman, and on the soundtrack of Woody Allen's Mighty Aphrodite.

In the years prior to his passing, Davern had put aside the saxophone to concentrate his efforts on the clarinet. Known for his acerbic wit on the bandstand, he was very much in demand worldwide for jazz festivals and concerts.

Like that of his mentors—Jack Teagarden, Louis Armstrong and Pee Wee Russell—Kenny Davern's playing was saturated with the feeling and tonality of the blues, whether he played a 12-bars blues or a pop song. Jazz critic Owen Cordle described Kenny Davern as “someone who touches the bluest feelings of longing” with his playing.

Kenny Davern with the Pee Wee Erwin Band on the bandstand at Nick's, 1959. Photo courtesy Kenny Davern.

On our show this week Kenny

gives us examples of this blues

feeling on a

never-before-broadcast track "C

C Rider," a traditional 12-bar

blues, and "Wabash Blues" and

"Baby Won't You Please Come

Home," both blues-inflected pop

melodies from the 1920s. Also on

the roster are the classic jazz

standards, Jimmie Noone's "Apex

Blues," "Farewell Blues" and W. C Handy's "St.

Louis Blues."

Photo credit for Home Page: Kenny Davern. Photo by Nancy Elliott, Courtesy Rutgers Institute of Jazz Studies.

Text based on Riverwalk Jazz script by Margaret Moos Pick ©2011