William Warfield. Photo courtesy Riverwalk Jazz.

On this broadcast, Riverwalk Jazz celebrates a triple crown of American music— Spirituals, Hymns and the Blues—with two celebrated figures in American music, and frequent guests on our broadcast series— flugelhorn and trumpet master Clark Terry and the renowned stage and screen actor William Warfield.

If Spirituals and the Blues are first cousins, then Hymns might be thought of as ‘second cousins once removed’. All three genres come from the same place in the human heart. As different as they may seem, all three are the expression of aching hearts and troubled minds. The Blues are secular Spirituals, or as T-Bone Walker put it, “The Blues are just Gospel turned inside out.”

Special guest Clark Terry is a great innovator of American music. He’s been a headliner at jazz events around the world, a pioneering jazz educator, and founder of the Clark Terry International Jazz Institute. Here, Clark talks speaks with series host David Holt about his childhood experience of Spirituals and Hymns growing up near a ‘Sanctified’ Church in his St. Louis neighborhood. At Sunday worship services, a heavy rhythmic beat emanated from the church—foot-tapping, hand-clapping, tambourines and singing—could be heard and felt by everyone in the neighborhood. Clark says these intriguing sounds he and other young people heard coming from that church gave them a great desire to get involved in music, one way or another."

.jpg)

Trumpeter Clark Terry with The Jim Cullum Jazz Band. Photo courtesy Riverwalk Jazz.

Clark Terry goes on to explain the origin of Charlie Parker’s “Hymn,” a 12-bar blues Terry and others have recorded many times. Terry recalls it was a Sunday tradition for the women of the congregation in African-American churches, such as the one in his St. Louis neighborhood, to respond to the preacher’s sermons with sustained, hymn-like humming in harmony. Clark remembers a serene, meditative piece Kansas City bandleader Jay McShann had in his repertoire, reflective of this improvised humming by the ladies of the congregation. The young Charlie Parker was a member of the McShann saxophone section at the time, and he took McShann’s melody at a much faster tempo to create his piece, “Hymn,” out of it.

“Come Sunday” was originally part of Duke Ellington’s extended 1943 symphonic work Black, Brown and Beige. The most enduring recording of Black, Brown and Beige, (including “Come Sunday”) was made by the Ellington Orchestra in 1958 with Clark Terry on flugelhorn/trumpet and Mahalia Jackson, "The Queen of Gospel" on vocals.

Jim Cullum says, “To my mind Hymns are not really that different from early jazz and blues. Musically, they’re simple and easy to sing or play. Often they have a pleasing, lilting quality. In 1980 we performed our first Jazz Mass. I thought it would be a one-time thing, but people responded so positively that we’ve now performed more than a hundred services in many different churches all over the country—Episcopal, Methodist, Catholic, Lutheran, Presbyterian, among others. It’s been something I really enjoy.”

"Let Us Break Bread Together" sheet music image courtesy Amazon.

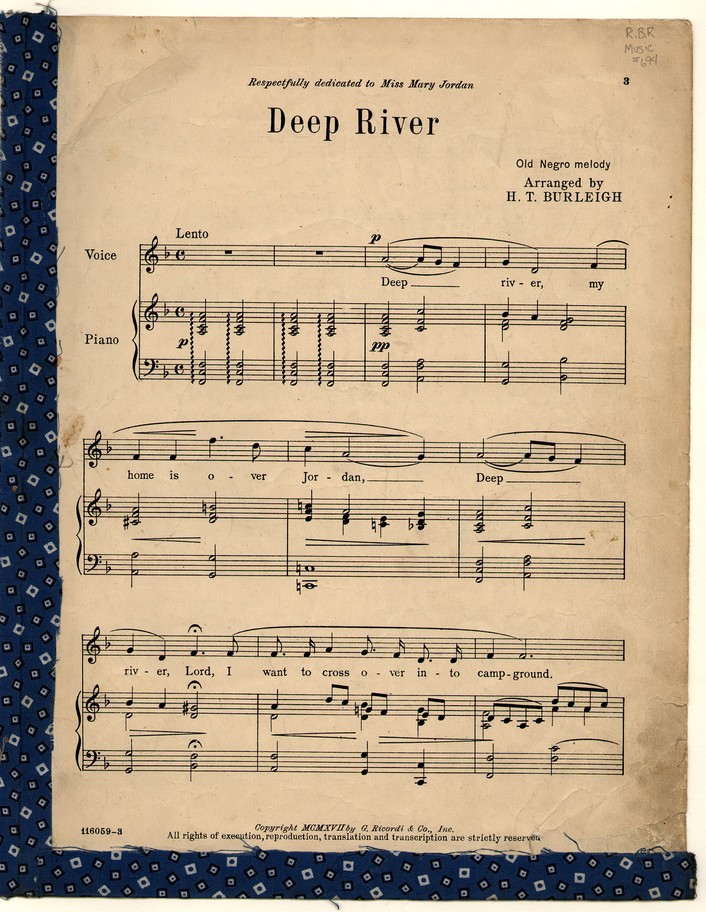

Many of the hymns typically performed for The Jim Cullum Jazz Band’s Jazz Mass are staples of the Methodist Hymnal, tunes like “Let Us Break Bread Together,” “Nobody Knows the Trouble I Seen,” “Deep River,” “Amazing Grace,” “All Glory Laud And Honor,” and “I Want Jesus To Walk With Me.” These venerable hymns have been given a jazz treatment by arranger John Sheridan and interpreted on our show this week by Clark Terry with Jim Cullum and his Band.

In conversation with host David Holt, theater and film legend William Warfield recalls his upbringing as the son of a Baptist minister in Rochester, N.Y. “In those days, the church thought that jazz and blues was just, you know, secular, the devil’s music.” Warfield describes how he would occasionally add a jazz or blues lick, as he played piano for services led by his father, and Warfield Sr. gazing down from the pulpit disapprovingly. Nevertheless William Warfield says, “Those were great memories for me. So many of us who came out of the Black tradition got our roots from the Church of God and Saints of Christ.

"St. Louis Blues" sheet music image courtesy Wikimedia.

Jim Cullum remarks, “Listening to the blues over the years, I’ve been struck by how much poetry you can hear in blues lyrics. “ On this broadcast, bandleader Cullum put together a piece with favorite blues lyrics from “Easy Rider Blues” “Big Joe Turner Blues” and “St. Louis Blues” for Mr. Warfield to interpret with the Band’s improvisation as background.

Series host David Holt recounts a childhood experience from his days growing up in Garland, Texas, near Dallas. One day, David and his brother found themselves picking cotton in the Texas sun one August day with an African-American picking crew. It was David’s first time hearing traditional Gospel songs sung by the workers. “I learned the value of music in life and how it can bring people together and make the work go easy.”

W.C. Handy was an articulate and insightful spokesman for the Blues. “Friendless Blues” is one of many Handy compositions often played by The Jim Cullum Jazz Band. Handy’s autobiography, The Father of the Blues, evokes the spirit of an entire generation of African-Americans, like himself—the grandsons of slaves. Spirituals and the Blues create the backdrop for his story:

W.C. Handy, age 19. Photo courtesy Wikimedia.

“The Blues is a thing deeper than what you’d call a “mood” today. Like the Spirituals it began with the Negro. It involves our history, where we came from, what we experienced. The Blues came from the man farthest down. Blues came from nothingness, from want, from desire, and when a man sang or played the Blues, a small part of that need was satisfied from the music. The Blues goes back to slavery—to longing. My father, who was a preacher, used to cry every time he heard someone sing the old Spiritual, “March On, I’ll See You on Judgment Day.” When I asked him why, he said, ‘that’s they song they sang when your uncle was sold into slavery into Arkansas.’

“The Blues fills longing in the hearts of all kinds of people. Now when you hear a white person sing the Blues he can put in it as much as a Negro. So long as it’s good it doesn’t matter whether it’s Negro or white, the Blues and Jazz have become a part of all American music, and it goes back to the Spirituals.”

"Deep River" music. Image courtesy library.duke.edu

In 1903 W.C. Handy was waiting for a train in Tutwiler, Mississippi. As the municipal bandleader in Clarksdale, Mississippi, he traveled from town to town throughout the Delta leading community bands playing Sousa marches and popular classical pieces in town squares. On this day, Handy was dozing on the platform at the depot when the Blues caught his attention for the very first time. Handy wrote:

“Life suddenly grabbed me by the shoulder and wakened me with a start. A lean, loose-jointed Negro had commenced plucking a guitar next to me while I dozed. His clothes were rags, his feet peeked out from his shoes; his face had some of the sadness of the ages. As he played, he pressed a knife onto the strings of the guitar. The effect was unforgettable. His song, too, struck me instantly—‘Goin’ where the Southern crosses the Yellow Dog.’ It was simply singing about going up to Moorhead where the Southern railroad track crosses the Yazoo Delta line, or ‘Yellow Dog,’ as it was known. This was not unusual. Southern Negroes sang about everything—trains, steamboats, mean bosses, fast women and stubborn mules. In this way, they set a mood for what we now call the Blues. Suffering and hard work were the midwives that birthed these songs. The blues were conceived in aching hearts.”

Photo credit for Home Page: Deep River CD cover image courtesy Riverwalk Jazz.

Text based on Riverwalk Jazz script by Margaret Moos Pick ©1994