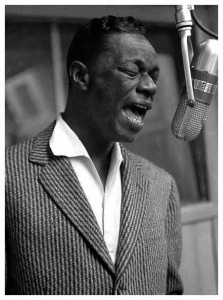

Nat Cole began his career in music in the 1930s as a hot young contender on jazz piano. His idol was the great Earl Hines and though Cole competed with Hines on jazz piano, Nat 'King' Cole would become a star for his unmistakable singing style—careful phrasing, a mellow tone and an intimate mood.

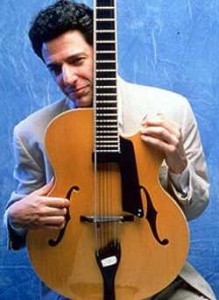

Joining us on the stage of The Landing for this week's tribute to Nat 'King' Cole is John Pizzarelli, critically acclaimed for his brilliant guitar work and smooth vocals. From Carnegie Hall to network TV, he's brought classic ballads to a new generation. Also on the bill is John's father jazz guitar legend Bucky Pizzarelli, a veteran of thousands of historic recording sessions with artists from Stephane Grappelli to Ray Charles and Benny Goodman.

Nathaniel Adams Coles was born in Montgomery, Alabama in 1919, the son of a grocery man who longed to be a preacher. In 1923 his parents joined the great wave of African Americans migrating north to Chicago. In the Windy City his father Edward James Coles became Reverend Coles and head of the True Light Baptist Church.

The Coles children learned to

play piano from their mother and

were recruited to sing or play

at their father's church. Just

around the corner they could

hear the tantalizing sound of

jazz bands wailing in clubs

along 35th and State Street on

Chicago's South Side. It wasn't

long before Nat and his older

brother Eddie were sneaking out

of their bedroom window at

night. Standing on the sidewalks

outside night clubs, they'd soak

up the sounds.

Chicago had an incredible variety of jazz in the early 1930s when Nat Cole was a boy. Fats Waller tickled the ivories at the Vendome Theater and New Orleans clarinetist Jimmy Noone jammed at the Midnight Club. Trumpeter Jabbo Smith was at the Panama Café and Earl Hines held forth at the Grand Terrace with his shiny white grand piano.

Just as he'd dazzled his parents by playing "Yes, We Have No Bananas" by ear when he was four years old, Nat applied the same technique to his study of jazz as a teenager. He listened to everything and took it all in. In high school he formed his own jazz band, The Rogues of Rhythm—and dropped the 's' from his last name. The Chicago Defender ran his photo at age 14 with the caption, "Plenty Hot! Nat Cole is the leader of one of the hottest bands of the Middle West!"

A year later, Cole faced a battle of the bands with his hero, the reigning king of jazz piano, Earl Hines. This time the Defender billed Nat as "Chicago's young maestro." It was Sept. 8, 1935 and 5,000 jitterbugging dancers packed the Savoy Ballroom as Cole's Rogues of Rhythm went head to head with the Earl Hines Orchestra. In the last set of the evening, Nat Cole stole the show playing Hines' signature song, "Rosetta."

Yet it took almost a decade for real success to come his way. In 1943 Capitol Records signed Cole's trio. Within a year, the Nat 'King' Cole Trio had their first major hit with "Straighten Up and Fly Right"—an original composition Cole wrote that was inspired by a folk tale his father used in his sermons.

1946 was a big year for Nat 'King' Cole. He was the first black American to have his own network radio show, on the air every Saturday evening. Nat's guests included stars like Mel Tormé, Pearl Bailey, Duke Ellington and Peggy Lee. And the Metronome magazine readers' poll named his trio the "best small combo of the year" and "the major influence on music of 1946." That December Cole had a monster hit with Mel Tormé's "The Christmas Song" which reached #3 on the pop charts. The only thing keeping it from #1 was Cole's own recording of "I Love You for Sentimental Reasons."

A year later, Nat made the transition from jazz pianist to singer. At the suggestion of his wife and manager he began to stand out in front of the band. By the end of 48 he had abandoned the trio format.

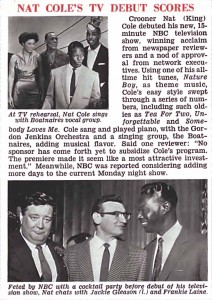

By 1956, ten years after the debut as the first black host of a network radio series, Cole became the first black American to have his own weekly network television series. Nat Cole was one of a handful of black performers to break through the racial barriers of the day and appeal to mainstream black and white audiences. Though his TV show lasted only one season, it remains a landmark in the world of broadcasting.

In the fall of 1964 Nat 'King' Cole knew he was dying of lung cancer, but he continued to perform. Cole finished what would be his last engagement at the Fairmont Hotel in San Francisco and entered the hospital a few days later.

A lifelong chain smoker, Nat 'King' Cole died on February 15, 1965 at the age of 45. At his funeral, Jack Benny offered this epitaph: "Sometimes death is not as tragic as not knowing how to live. This man knew how to live—and how to make others glad they were living."

Photo credit for home page teaser image: Legendary Nat King Cole. Photo courtesy kalamu.

Text based on Riverwalk Jazz script by Margaret Moos Pick ©2009