Nothing gets in the groove like a catchy ‘riff.’ The hot rhythm of a good riff lifts us out of our seats and onto the dance floor. Riffs are one of the building blocks of jazz. They are everywhere—as background figures, parts of jazz solos, and even entire riff tunes.

A riff is a short melody—just a few notes—repeated over and over in a rhythmic manner. The origin of the riff can be traced to early African-American gospel and blues forms where short, repeated, chant-like melodic fragments were typically sung or played as a background figure to support a soloist. The jazz riff evolved out of this call-and-response practice.

With their New York debut at Harlem's Savoy Ballroom in the late 1930s, the great Count Basie Orchestra and their riffing style breathed new life into the Swing Era. It is said that in rehearsal Basie would send each section of the band into a separate room, charged with the task of coming up with their own new riff. These sectional riffs would later be combined to create a shouting call-and-response effect. The result—riff tunes like "One O'clock Jump" with its famous final 'shout' chorus.

The Count Basie Orchestra at the Famous Door in New York, late 1940s. Courtesy Good Morning Blues: The Autobiography of Count Basie, Albert Murray.

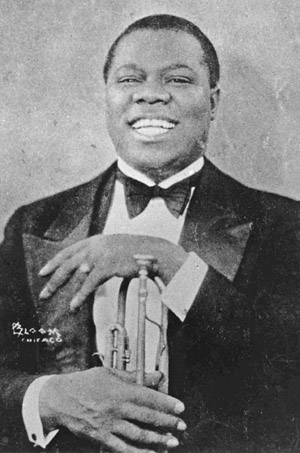

Louis Armstrong, whose pioneering genius inspired generations of jazz musicians from the 1920s to the present day, often used riffs in his solos to build tension. A good example of Louis' solo riffing can be heard on his 1929 Okeh recording of "St. Louis Blues." As an added attraction to his big-band dance concerts, Benny Goodman often featured small combinations—or combos—of three to six pieces. The later Goodman small combos, featuring guitarist Charlie Christian, developed many riff-based tunes like "Gilly," named after Goodman's daughter.

This week on Riverwalk Jazz The Jim Cullum Jazz Band uses simple, familiar riffs to build entire arrangements and tunes—from originals like “Keep Off the Grass” to standards like “Dinah.” Special guest Bob Barnard joins the band on trumpet.

Riffs are really very simple,

infectious melodic ideas. There

is a 'chant-like' background

figure in the Band's

interpretation of "Perdido

Street Blues" that’s a good

example of how the riff' began

to evolve in early jazz. Sitting

in on cornet special guest Bob

Barnard helps brings back the

hot, riff-based sounds of New

York's 1930s jazz mecca—52nd

Street—on "Undecided," a tune

star trumpeter Charlie Shavers

wrote for small combos of the

day.

Jim Cullum talks about what it

was like for a new player

joining the Count Basie Band

when there were no written

musical arrangements of the

Band's repertoire. Trumpeter

Harry 'Sweets' Edison described

the process years ago on one of

our Riverwalk radio shows.

Shortly after Edison started

working for Basie, Sweets

complained to him that he wanted

to quit because he felt lost on

the bandstand. Sweets couldn’t

find his place in the Band,

meaning he couldn’t find harmony

notes on the riffs that weren’t

already being played by another

player. Basie told Sweets

Edison, “If you find a note

tonight that works play the same

damn note every night.”

Photo credit for home page teaser image: Harlem Dancers Leon James and Willa Mae Riker. Photo courtesy The Swing Era by Time-Life

Text based on Riverwalk Jazz script by Margaret Moos Pick ©2010