This edition of Riverwalk Jazz tells the story of Louis Armstrong’s rise to stardom in the 1930s with Nicholas Payton, a hot young trumpet player from New Orleans, joining The Jim Cullum Jazz Band on the bandstand at The Landing. The son of bassist Walter Payton, a devotee of Louis Armstrong, and a professional musician since the age of twelve, Nicholas Payton was a Verve recording artist and featured soloist with the Lincoln Center and Carnegie Hall Jazz Orchestras, at the time of this broadcast.

In the Thirties, Louis Armstrong stepped onto the world stage, as a mainstream artist and entertainer. Crooner Bing Crosby called Louis Armstrong “the beginning and end of music in America.” Miles Davis confessed, “You know, you can’t play anything on the horn that Louis hasn’t played.” Duke Ellington once said, “I loved and respected Louis Armstrong. He was born poor, died rich, and never hurt anyone along the way.” Jim Cullum says, “Here we are in the post-millennial era, and his influence is so profound, we can’t get through a set without playing something from the vast repertoire of Louis Armstrong.”

King Oliver. Photo courtesy Red Hot Jazz.

For millions of people Louis Armstrong lived up to his own myth. He grew up in the poorest, filthiest slum in New Orleans, a black child with no father, in a society that had no tolerance for the color of his skin. His genius and the power of his art transformed his life, and continues to inspire us today. Though Armstrong’s performing career spanned some six decades, more than fifty years after he died, his recorded performances are often heard on movie soundtracks, in television commercials and on the radio.

Playing with King Oliver at the Lincoln Gardens in Chicago, and later with Fletcher Henderson’s popular dance band in New York, Louis Armstrong emerged as a highly inventive jazz soloist in the 1920s. In the 1930s he developed a sparser, leaner style noted for his incredible high note playing. Louis was well on his way to becoming an American superstar. In the process, he migrated from a straight diet of jazz and blues, taking on pop songs of the 30s, like “He's a Son of the South,” and making them swing.

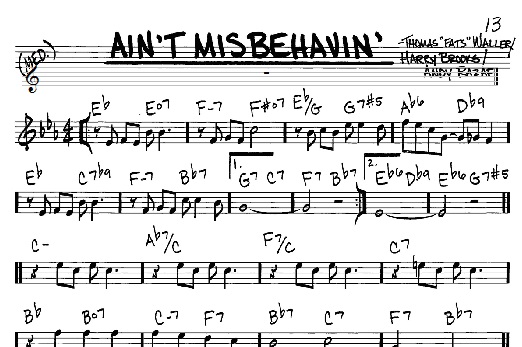

1929 was a breakthrough year for Louis Armstrong. Headlining in the popular New York revue Hot Chocolates, Armstrong had a crossover hit record with the Fats Waller-Andy Razaf tune, “Ain’t Misbehavin.’” For the first time, Armstrong’s genius touched audiences outside the jazz world, and he developed a mainstream following among white fans. Armstrong’s unique singing style on pop tunes, coupled with his virtuoso trumpet playing, created a magical combination that set the stage for his future superstardom. Louis was destined not only to be a stellar instrumentalist but also a successful actor, singer and entertainer.

Buddy Bolden photo in public domain.

Throughout it all, Louis Armstrong stayed deeply attached to his roots in New Orleans jazz and blues though it wasn’t always apparent to all his fans. He always said, “There’s no such thing as a bad tune,” meaning that a musician ought to be able to take any piece of music and make it sound good. He’d say, “Don’t listen to the tune I’m playing, listen to the notes I’m playing.” Armstrong delved into pop material that other jazz players might avoid. Late in life, he caught heat from jazz critics for his eclectic taste, playing tunes like his monster hit “Hello, Dolly!” Armstrong made the point that no matter what he played, he always heard New Orleans jazz giants, like his mentor King Oliver, Lorenzo Tio and Buddy Bolden, in the back of his mind. Louis often said, “When I play my music, that’s what I’m listening to.”

Lorenzo Tio

Caught in a struggle between rival mob bosses who controlled the nightclub scene in New York and Chicago, Armstrong avoided the jazz scenes there and stayed on the road in the early 1930s. He often headlined as a star soloist with backup bands to avoid being forced to play with some mobster’s gun at his back. It was the autumn of 1931 when Armstrong stopped off in Chicago for a recording session and cut a series of memorable sides including the number that would become his theme song, “When it’s Sleepy Time Down South.“

Armstrong made his first trip to California for an extended booking at Frank Sebastian’s New Cotton Club in Culver City near Los Angeles a year earlier in 1930. The drummer in the local backup band at the club was a kid named Lionel Hampton. Armstrong predicted, “this kid on drums is bound to make it big someday.” Listening to live broadcasts from Sebastian’s Cotton Club, the Hollywood crowd fell in love with Armstrong’s playing, and Louis received his first of many movie offers. He made the highly forgettable film Ex-Flame, which has long since disappeared. And, on this trip to the West Coast, Armstrong cut his last recording as a sideman; he backed country singer Jimmie Rogers on the fascinating side, “Blue Yodel Number Nine.”

Louis Armstrong in front of Sebastian's Cotton Club. Photo in public domain.

The 1930s was a fertile period for Armstrong. He made many of his most stunning jazz records including, “I'm A Ding Dong Daddy From Dumas,“ “Shine” and “Memories of You.” On the session for “Memories of You,” Louis Armstrong and drummer Lionel Hampton discovered a new instrument, the vibraphone, stowed away in the corner of the studio. Lionel tried it out, and Armstrong insisted he use it on the opening phrase of “Memories of You.” It was the first recorded vibraphone solo in jazz, and before long Hampton would build a career as the “Vibes President of the United States.”

Armstrong’s stay in California ended in trouble. He and a pal were caught smoking marijuana in the Cotton Club parking lot. A law outlawing marijuana use had just been passed, and it turned out that Armstrong was the first high-profile “celebrity” prosecution and conviction. Armstrong’s six-month sentence was eventually suspended, but as part of the deal he had to spend his nights sleeping in the jail hospital. He made a public statement that he would never use the newly illegalized weed again; though he continued to be a devoted user for the rest of his life.

Louis Armstrong, 1932. Photo in public domain.

It was during this period in California that Louis began to seriously experiment with ballads. Among others, he recorded the tunes “Body and Soul” and “(If I Could Be with You) One Hour Tonight.” Jim Cullum says, “To my way of thinking his work as a balladeer reached a high point when he composed and recorded ‘If We Never Meet Again’ with lyricist Horace Gerlach. It shows great variety, and depth of feeling.”

When Armstrong left California his marriage to his second wife Lil Hardin was on the rocks, and he was embroiled in a complicated management dispute that continued to make trouble for him with the mob in New York and Chicago. On his way to New York, he stopped off in Chicago for a gig at a club called the Show Boat. According to Louis, he didn’t have any idea that two rival mob bosses were still feuding over his management contract. The New York outfit sent over some heavies to scare Louis into leaving the Show Boat and taking a job he didn’t want at Connie’s Inn in Harlem. One night, the tough guys from New York started a fight on the dance floor in front of Armstrong. The story goes that Louis kept playing his horn, as he always did with his eyes closed, ignoring the battle under his nose. The next night, a gangster whispered into his ear, “Someone wants to talk to you in the dressing room.” It was a tough guy sitting in the dark with a pistol in his hand. “You’re going to New York,” the heavy said. “You’re leaving on the first train tomorrow morning and you’ll be playing at Connie’s Inn tomorrow night.” Defying the gangster’s demands, in the dead of night, Louis boarded a train heading south, and surfaced in Louisville, where he led the first black band to play at the Kentucky Derby.

Pennies From Heaven movie poster. Image courtesy Wikimedia

When Louis Armstrong returned to New Orleans for the first time since making it big, he was welcomed like a hero in his hometown. He paid a visit to the Colored Waifs’ Home where he had received his first music lessons as a kid. He spent time with Captain Jones, the head of the Home, who had given Louis his first cornet. Louis sponsored a hometown baseball team—Armstrong’s Secret Nine. Soon after, he left for his first European tour.

Louis Armstrong toured with great success in England, Europe and Scandinavia and continued to make spectacular recordings. In 1936 he appeared with Bing Crosby in a major Paramount film, Pennies from Heaven.

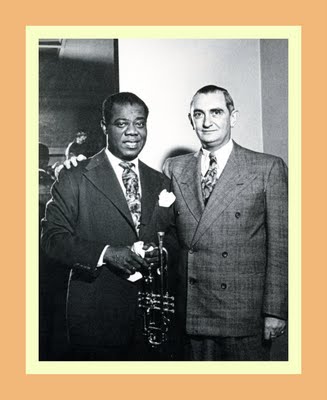

Louis Armstrong and Joe Glaser. Photo in public domain.

The following year he became the first black entertainer to host his own network radio series. By the end of the decade, Louis Armstrong was established as a major international star. And, he was engrossed in two key relationships that would last to the end of his life, some thirty years later. Joe Glaser, the dynamic promoter and talent manager, took over the business side of Louis’ career and kept him out of trouble with the mob. Armstrong fell in love and married Lucille Wilson, a gorgeous young dancer at the Cotton Club in New York, who Louis called “Brown Sugar.”

Jim Cullum says, “In the 1930s, Louis entered phase two of his multi-faceted career. His bubbling, magical personality was fully developed, and his clear, swinging upper-register trumpet playing was different than the earlier Louis, but just as great. With it, he inspired the Swing Era. All those big-band brass section riffs were mainlined straight from Louis…he seemed to go happily through life. His love of life and his music were there at every turn. He thrills and inspires us like no one else in jazz history.”

Trumpeter Nicholas Payton. Photo courtesy of the artist.

Our special guest, New Orleans trumpeter Nicholas Payton tells series host David Holt he knew of Louis Armstrong as a child but was seventeen when he really discovered Armstrong’s music. It was his bass-playing father, Walter Payton, who encouraged Nicholas to take a serious look at Armstrong’s playing. Nicholas says of Armstrong, “The spirit and vitality of the music is timeless. The freshness he played with back then remains innovative today. There are things Louis did back then that no one has dealt with since…you can’t get away from Louis Armstrong, if you’re going to play jazz. His influence is embedded into jazz forever, that’s just the way it is.”

Nicholas has this advice for novice musicians and their parents: “When you’re starting out, you have to be tolerant of sounding bad at first. You have to practice through that stage, and hopefully you’ll be able to play one day.”

Radio Show Playlist Notes:

“Mahogany Hall Stomp“ is a classic New Orleans-style tune Louis played throughout his career, named after the infamous early 20th century Storyville brothel.

“Tiger Rag“ is a quintessential New Orleans march of uncertain origin, recorded many times by Louis Armstrong.

“Hustlin' and Bustlin' For Baby,“ as performed here, features a vocal by The Jim Cullum Jazz Band banjoist Howard Elkins.

“I Gotta Right to Sing the Blues,“ composed by Harold Arlen and Johnny Mercer and frequently performed in Armstrong’s repertoire, was eventually adopted by trombonist Jack Teagarden as his theme song.

“Some Of These Days“ and “Swing That Music“ were both recorded by Armstrong in the 1930s in high-powered virtuosic versions recalled here by guest Nicholas Payton sitting in with The Jim Cullum Jazz Band. “Swing That Music” is an Armstrong original.

Photo credit for Home Page: Louis Armstrong, 1930. Photo courtesy songbook1.wordpress

Text based on Riverwalk Jazz script by Margaret Moos Pick ©1995