James Reese Europe with bandmembers. Photo courtesy of The National Archives.

This week’s edition of Riverwalk Jazz, From Lenox Avenue to Broadway, celebrates the influence of Black Musical Theater on Broadway in the 1920s and 30s. Special guests are the Obie award-winning actor, singer and playwright Vernel Bagneris and piano master Dick Hyman.

On a bright February morning in 1919, the African-American heroes of the 369th Infantry Regiment marched in triumph up Fifth Avenue in Manhattan and on home to Harlem. From the battlefields of World War I to the streets of New York City, Lieutenant James Reese Europe led his regimental band. High-stepping in front of the marching musicians, the Drum Major was none other than the popular tap dancer and vaudeville entertainer Bill “Bojangles” Robinson.Twenty-nine hundred black soldiers marching in tight formation up the avenue, made an awe-inspiring sight for thousands of New Yorkers lining the parade route. Dubbed the ‘Harlem Hellfighters’ by their German foes, the unit’s victory march made front-page news in The World with the headline, “Swinging Up the Avenue.”

The 369th Infantry Regiment marching up Fifth Avenue, 1919. Photo courtesy Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture.

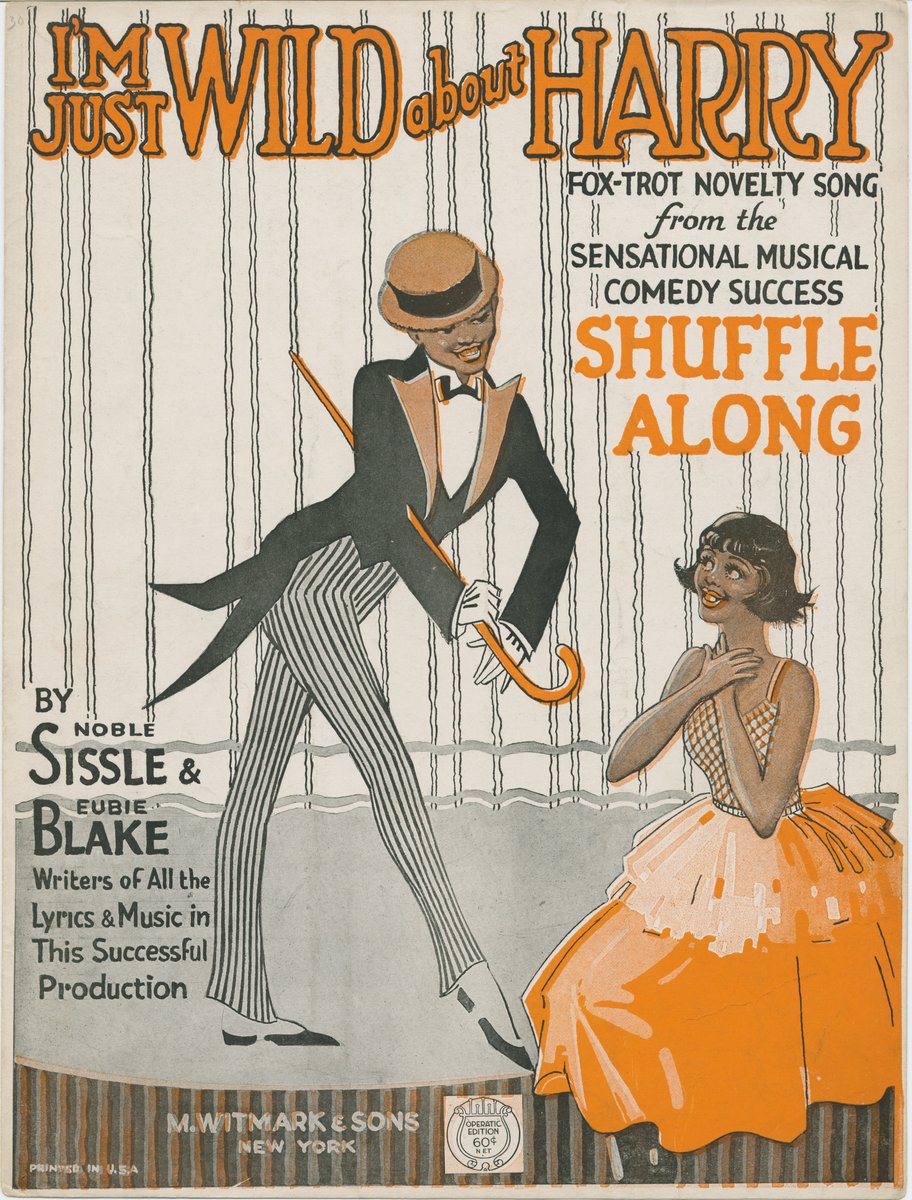

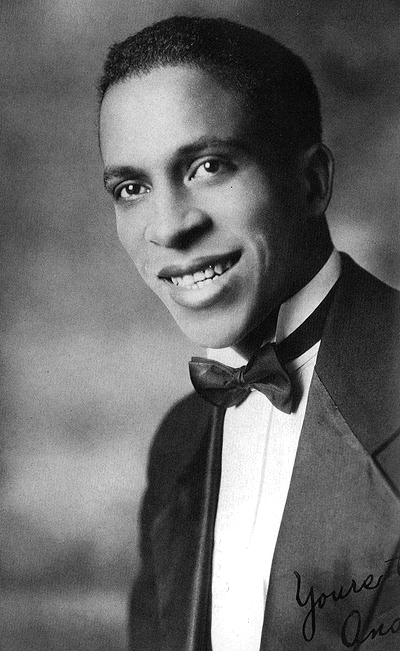

Just a few days later, Big Jim Europe and his regimental band made history again—this time in the recording studio with a tune that would become a top hit of 1919, “How You Gonna Keep ‘Em Down on the Farm (After They’ve Seen Paree?)” The band’s vocalist Noble Sissle was destined to revolutionize American musical theater along with his partner, the ragtime pianist and composer Eubie Blake. In 1921 Sissle and Blake raised the curtain on their musical Shuffle Along, breaking box office records and racial stereotypes in one stroke.

1921 sheet music image courtesy of Wikimedia.

Shuffle Along, written and performed by hip young African-Americans, was the first financially successful all-black show on Broadway. Never before had a popular revue so cleverly celebrated—rather than exploited—black creativity. The show’s biggest hit song “I’m Just Wild about Harry” is performed here by The Jim Cullum Jazz Band with Dick Hyman sitting in on piano. Another musical number from the revue, “Love Will Find a Way,” dared to show audiences the first stage kiss, played straight for sentiment rather than laughs, by black actors on the Broadway stage. So deeply engrained was the taboo against portraying romantic love between black actors, Sissle and Blake confessed their concern that they might all get booed off the stage on opening night.

By the time Shuffle Along opened in New York in 1921, everyone in Harlem seemed to know at least one person in the cast. Packed with fresh, new talent, the show launched a number of important black artists. Singing and acting giant Paul Robeson was best known as a football star before he got a bit part in Shuffle Along. His brief appearance onstage opened the door to an important role for him in Eugene O’Neil’s The Emperor Jones. Josephine Baker sparkled in the chorus line and went on to star in Sissle and Blake’s next production Chocolate Dandies; and then she rocketed to stardom with her sensational act (wearing her famous ‘banana skirt’) in the Follies Bergere in Paris.

Eubie Blake and Noble Sissle, 1926. Photo courtesy of the Frank Driggs Collection.

Imitators following in the wake of Shuffle Along, tried to capitalize on the demand for black musical theater. The songwriting team of Henry Creamer and John Turner Layton opened their revue Strut Miss Lizzie, a showcase for their acting talents as well as their tunes, at a little place in Harlem in 1922. Unfortunately, the funds were not available to keep the show afloat for long and it closed after a short run at the Times Square Theater. Though Miss Lizzie couldn’t touch the success or creativity of Shuffle Along, the score contained two memorable hits. Initially discarded from Lizzie, Creamer and Layton’s “Way Down Yonder in New Orleans” was well on its way to becoming an American classic later that same year, when it was interpolated into the more successful revue, Spice of 1922. The title tune “Strut Miss Lizzie,” a hot jazz standard recorded by Bix Beiderbecke, Jack Teagarden, Benny Goodman and many others in the 1920s and 30s, remains a staple of early jazz specialists and is heard here performed by The Jim Cullum Jazz Band.

.jpg)

Vernel Bagneris. Photo courtesy of the artist.

After Shuffle Along, American music and musical theater could never be the same. Audiences wanted the edge and fun of jazz and blues. The influence of this new music performed by black artists was seen everywhere. Sentimental parlor songs, a staple of vaudeville repertoire, took a back seat to numbers like “He May Be Your Man But He Comes to See Me Sometimes.” Insulting blackface and “poor tramp” costumes of the minstrel show tradition slowly faded away. In advertising Strut Miss Lizzie, the show’s writers and stars Creamer and Layton promoted “Way Down Yonder in New Orleans” as a southern song “without a mammy, a mule or a moon.” On this broadcast, The Jim Cullum Jazz Band performs “Way Down Yonder” with Vernel Bagneris on vocals and piano master Dick Hyman.

In 1929 the hottest ticket in New York was a show at the Hudson Theater written by Fats Waller, Harry Brooks and Andy Razaf called Hot Chocolates. The critics loved the raunchy comedy and the jazzy score—with sassy numbers like “Ain’t Misbehavin’.” But “Black and Blue” was an unlikely song to be included in a frothy revue. Vernel Bagneris introduces his performance of the tune with Dick Hyman on piano by telling the story of how “Black and Blue” came to be written:

Andy Razaf. Photo courtesy Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture.

“Andy Razaf was a prince from Madagascar, but upon arrival in America he was just another Negro and treated accordingly. He was working on a new show called Hot Chocolates. The money had been put up by a gangster named Dutch Schultz. During the previews Dutch Schultz tells Andy Razaf to write a funny song for a colored girl about how difficult it is being colored. Andy Razaf says ‘No, I’m not going to write the song.’ Dutch Schultz slams him up against the wall, cocked pistol pressed to his skull and says, ‘You will write the song, boy.’” The result was a lyric and song with a clever subterfuge, a double meaning. “What Did I Do to Be So Black and Blue?” later became known as the first racial protest song. For the show’s opening, Razaf succeeded in satisfying the gangster and easing his threat.”

Fats Waller’s “Ain’t Misbehavin’” became the runaway hit of the season. Every character in the revue sang a chorus of the catchy tune at some point in the show. The highlight of the evening was Louis Armstrong’s performance as he stood up in the orchestra pit, a spotlight picking him out of the dark, and played his unmistakable trumpet solo. Bagneris says, “No one could leave the theater without humming the tune.” Armstrong’s recording that year was a breakthrough hit for him. Here, Vernel sings FatsWaller’s classic with The Jim Cullum Jazz Band and Dick Hyman on piano.

.jpg)

"Ain't Misbehavin'" sheet music, 1929. Image courtesy of songbook1.wordpress.

George Gershwin, Irving Berlin and Jerome Kern were among the many white songwriters to be influenced by the new music migrating from Harlem to Broadway in the early 1920s. Dick Hyman comments, “In those days everyone was trying to write a hit blues song, like Eubie Blake and the other black composers had written.” Hyman plays examples of these songwriting efforts, including George Gershwin’s “Piano Prelude No. 2,” a piece composed in the 12-bar blues form whose melody suggests an earlier song by W.C. Handy, “Aunt Hagar’s Chillun’s Blues.” Dick Hyman also demonstrates how Irving Berlin’s “Home Again Blues” has a boogie-woogie bass pattern in the left hand. And, Hyman follows it up with a demo of how Jerome Kern’s verse to “Can’t Help Lovin’ Dat Man,” from his 1927 musical Show Boat, suggests the bluesey influence of Gershwin. To further illustrate the point, Dick Hyman and John Sheridan play a duo piano version of George Gershwin’s “Sweet and Low Down,” for which Gershwin wrote a boogie woogie bass pattern recalling Harlem rent parties.

George Gershwin. Photo courtesy of songbook1.wordpress.

At the time of his early success between 1920 and 24, George Gershwin wrote more than thirty songs for George White’s annual Scandals revues on Broadway. These revues were flashy shows full of big production numbers. “I'll Build a Stairway To Paradise” was just such a tune, created for the 1920 Scandals. When Gershwin played it for himself, it too was transformed into a boogie woogie. Here Dick Hyman offers his homage to Gershwin.

Broadcast Playlist Notes:

“I Had To Do It,” featuring Dick Hyman and Vernel Bagneris with Jim Cullum and the Band, was created in 1938 by Fats Waller and Andy Razaf.

.jpg)

Dick Hyman. Photo courtesy of the artist.

“Capricious Harlem” is by Shuffle Along composer Eubie Blake, also a piano virtuoso in the ragtime style. Dick Hyman presents his solo performance.

“I Wonder Where My Sweetie Can Be” was a typical vaudeville number from the act of The Dixie Duo—Noble Sissle and Eubie Blake. Our version is a duet featuring Dick Hyman and Vernel Bagneris on vocals.

“Juba Dance,” from 1913, was written by Nathaniel Dett, a black composer who was a classical musician. Here Hyman and Sheridan perform it on duo pianos. “You can hear the influence of something like stride piano,” says Maestro Hyman.

Photo credit for Home Page: Vernel Bagneris. Photo by Jamie Karutz.

Text based on Riverwalk Jazz script by Margaret Moos Pick ©1996