An Appreciation By Don Mopsick

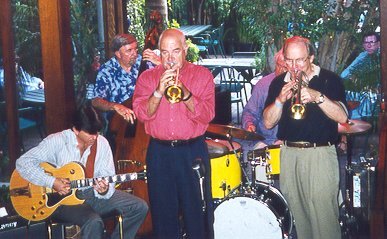

Over almost two decades with The Jim Cullum Jazz Band, I've been lucky to work and record half a dozen times with the great Australian cornet player Bob Barnard. Bob's a fun guy to be around and has a relaxed attitude toward life.

Allow me to explain why Bob is considered a "musician's musician:" by example, Bob teaches us that in order to truly play jazz, you've got to bring along your chops.

The first thing that grabs a listener about Bob's playing is his beautiful sound. Like his self-avowed models Louis Armstrong and Bobby Hackett, Barnard has mastered the art of "filling up the horn," making the most of the air that he puts into it. With such an elegantly efficient technique, the music pours out of him, seemingly without effort. Think of a tennis champ who long ago found the "sweet spot" of the racquet.

Second, Bob's improvised jazz choruses are so perfect in form and execution that you might think they're composed. They're not.

While the influence of Armstrong in his jazz playing is clear, it's not an end but a beginning for Barnard. Barnard has an expanded—one can say "chromatic"—harmonic language which he puts to good use by building on, say, a phrase he may have heard on an old Hot Five record decades ago. Barnard has made Armstrong his own; he's far from a re-enactor.

The obvious model for his ballad conception is Bobby Hackett. Both Hackett and Barnard share a tuneful, vocal approach to ballads. The artistry of any balladeer in jazz, or jazz-inspired pop, lies in the subtlety of pitch-bending in the service of blues tonality. For this skill the singer or instrumentalist needs complete control over the instrument, be it a brass embouchure or a set of vocal pipes. This is echoed by Barnard in a Riverwalk Jazz interview where he talks about how much more vulnerable the brass balladeer can be compared with the other instruments.

All of these elements come together in Barnard's "hot" playing, with the extra added dimension of a powerful, nuanced attack. In music, "attack" refers to the start of a given note, on a brass instrument done with the tongue releasing the air column as in the syllable "tu." In jazz music-making attack is a critical, defining element. Just as jazz brass players love to shade their sound by using mutes in the bell, they also cultivate the art of coloring the attack by pronouncing many different syllables.

What's more—in jazz, the attack is the brass player's drum beater. And like a drummer, the player projects a happy, dancing feel of swinging rhythm by artfully choosing where to place his notes within the beat. Barnard's attack is right out of Armstrong, perhaps the most "intentional" and unambiguous rhythmic concept in all of jazz.

This happy, confident feeling of hot rhythm pioneered by Armstrong is a standard to which all jazz musicians have been aspiring ever since he came on the scene, and we admire Bob Barnard for getting closer than most.

Photo credit for Home Page: Australian Jazz Man Bob Barnard. Photo courtesy Riverwalk Jazz.

Text based on Riverwalk Jazz script by Margaret Moos Pick ©2012