A moveable feast of articles, interviews and reviews on seminal figures who advanced the art of jazz in the early decades.

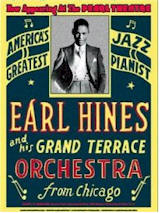

The ‘Fatha’ was the Daddy of Them All

Earl ‘Fatha’ Hines has been

called the first modern jazz

pianist.

Earl ‘Fatha’ Hines has been

called the first modern jazz

pianist.

Good luck brought Earl Hines and Louis Armstrong together in 1926 when they met by accident at the local musician's union hall in Chicago. The two soon-to-be jazz legends became great friends, and Hines worked briefly in Louis Armstrong's Stompers. Their friendship resulted in a series of spectacular recordings made in 1928, including the famous Hot Five and Hot Seven sessions that produced "West End Blues."

Here Siegfried H. Mohr, an expert in historical jazz piano styles, offers an excerpt of his interview with Earl Hines first published in Le Jazz Hot magazine in Paris in the 70s.

Mohr asked Earl Hines about his association with Louis Armstrong.

Hines: Now, Armstrong and I have always been buddies from the beginning. We went into the Sunset Cafe together with Carroll Dickerson's Orchestra in the spring of 1926, see? This was right across 35th Street (on the south side of Chicago) from the Plantation Cafe where King Oliver was playing. Louis and I ran around together. We were inseparable the whole time we were in the Sunset. There's nothing much to be said other than we were like two brothers.

Mohr: Your famous 'trumpet piano style' of playing was strongly featured in those Armstrong dates. How did you evolve that?

Hines: Well, you see, it so happens that a lot of people don't tell the truth about it coming from me. I wanted to play cornet but at that time they didn't have this system of non-pressure. I picked the doggone thing up and blew it and it used to hurt me behind my ears.

Hines: Well, you see, it so happens that a lot of people don't tell the truth about it coming from me. I wanted to play cornet but at that time they didn't have this system of non-pressure. I picked the doggone thing up and blew it and it used to hurt me behind my ears.

When I got to Chicago I was amazed

to find a trumpet player like Louis

who was playing the things that I

wanted to play. We were actually

playing the same things, the same

style. Only he was playing it on

trumpet, I was playing it on piano.

We used to copy from each other—if

he used to make a run I'd steal it

and say ‘thank you.’ And I'd make

one and he'd steal it and say ‘thank

you’. That's how my trumpet style

piano came about. People think that

I got it from Armstrong but l

didn't! I was playing this way

before I met Louis. When I made the

records with him, I was already

playing like this. People have

misunderstood that, not that I feel

envious toward Louis—I don't mean it

that way. I just want to let people

know that there are other people

that were involved in my getting

that particular style—Joe Smith and

Gus Aiken, you see—but these

musicians were unknowns.

When I got to Chicago I was amazed

to find a trumpet player like Louis

who was playing the things that I

wanted to play. We were actually

playing the same things, the same

style. Only he was playing it on

trumpet, I was playing it on piano.

We used to copy from each other—if

he used to make a run I'd steal it

and say ‘thank you.’ And I'd make

one and he'd steal it and say ‘thank

you’. That's how my trumpet style

piano came about. People think that

I got it from Armstrong but l

didn't! I was playing this way

before I met Louis. When I made the

records with him, I was already

playing like this. People have

misunderstood that, not that I feel

envious toward Louis—I don't mean it

that way. I just want to let people

know that there are other people

that were involved in my getting

that particular style—Joe Smith and

Gus Aiken, you see—but these

musicians were unknowns.

Hines: They were nothing but standard tunes, with the exception of his originals. Louis and I, we just enjoyed each other's work. Louis was a happy-go-lucky fellow and so was I and we ran around together. It just so happened that I was playing things similar to the things he was playing. I used octaves and played the piano like a trumpet rather than a whole lot of fingering like other guys were doing on piano at the time. They were playing ragtime stuff. I wasn't doing that. When I was in the band I thought of myself as another instrument similar to the horns—in other words I used to team up with the other horns with my right hand, see? That's the reason why they call my playing that, trumpet style.

Mohr: Were there any idols that you had on your instrument at that time?

Hines: Well, the best danceable, best likeable music I found during those days was in nightlife. The nightclubs were playing the kind of music that lasted because it had the blues effect. People out late at night wanted someplace to go to tap their feet or listen to beautiful ballads.