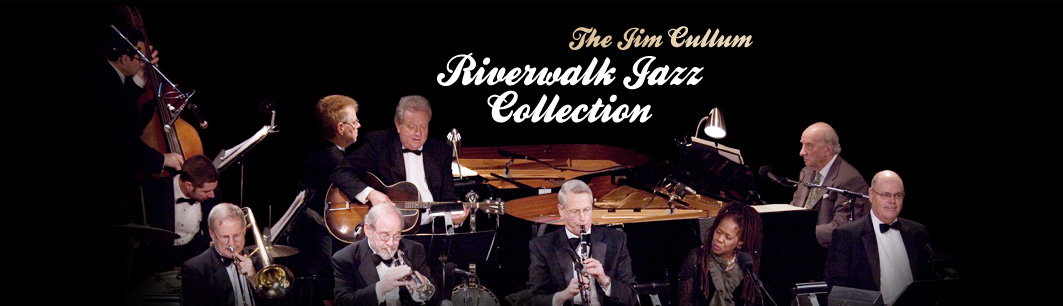

Jim Cullum Jr. is the leader of the

Jim Cullum Jazz Band and proprietor

of the Landing Jazz Club on the

Riverwalk in downtown San Antonio.

Jim is also the co-producer of the

Riverwalk Jazz public radio

series.

Jim began playing cornet in 1955 at

age 14. Fascinated with the records

of legendary cornetist Bix

Beiderbecke, Jim was at first

self-taught. In high school he

organized his fellow musicians into

after-the-game dance bands. While

attending college, Jim began a

partnership with his clarinetist

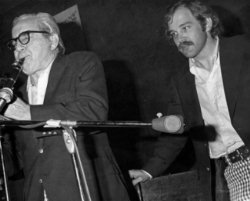

father, the late Jim Cullum, Sr.,

forming a seven-piece traditional

group they called the Happy Jazz

Band.

Jim Sr. was born in Dallas and had

two careers—one in the family

grocery business and another as a

jazz reed player. During the 1930s

he worked in bands led by Jack

Teagarden, Jimmy Dorsey and Adrian

Rollini.

Part of my fascination with jazz

came from a desire to please and win

the respect of my father and mother.

This desire certainly lay beyond

consciousness, for when I began

discovering jazz I was a typical

early adolescent and would never

have voluntarily done what my

"prehistoric" parents wanted.

But I always admired them. They were

tangled up with jazz in a big way

and like any wild adventure, theirs

was a life of extremes. They had

lived the craziest, wackiest, most

romantic life and had the most

fun—at least so it seemed to me.

Ernest Hemingway had nothing on my

fun-loving father. But for a few

years beginning in about 1949, life

performed one of its inevitable

flip-flops and things weren't quite

as much fun anymore. Dad was 35 that

year.

Oh, he didn't give in easily. In

fact, even on an off day, he still

seemed to have a lot of fun. He had

a built-in ability to laugh at life.

An example: one day while we were

still living in Dallas, I went along

while Dad hung out at the "Pink

Elephant Lounge" with his drinking

buddy, drummer Bob McClendon. Still

young men, they were handsome and

well-dressed. They always reminded

me of a Hope and Crosby "Road"

movie. The Pink Elephant was aptly

named as it catered to hard-core

drinkers. In compliance with Texas

liquor laws of that time, The Pink

Elephant served only beer and

set-ups, but its owner ran a small

liquor store in the building next

door so customers bought distilled

spirits by the pint or fifth. The

Elephant action would start during

the late morning, about 11:00 AM,

with a few regulars struggling in

for "hair of the dog."

One day at the Pink Elephant, I was

on hand to witness Dad and McClendon

in a classic which started when Dad,

laughing and very much in the spirit

of the moment, dropped McClendon's

hat on the floor and stomped on it.

Wow! Take that! (He had been joking

about the style of the hat for

weeks.) With that, McClendon reached

over and picked up a large pair of

shears that happened to be lying on

the bar and cut off Dad's tie. To

make this more interesting, it was a

cold day and the heat wasn't on in

the Elephant. They stood in their

overcoats facing each other in a

Laurel and Hardy stance and

gradually tore and ripped off each

other's coats and shirts. One would

stand and look on as though

defenseless while the other seized a

piece of cloth like a suit breast

pocket. In a downward

thrust—rrrrrip—off would come the

pocket. It went on and on to the

astonishment of the bartender and

the other Pink Elephant customers.

Eventually we left for home, Dad

still laughing to himself. But the

other side of all this gradually

began to emerge. Dad and McClendon

were constantly playing practical

jokes on each other. The distributor

cap would be taken off the car or

the electric power or water would

get turned off. Twenty chicken

dinners were delivered. At this

stage my mother was worn out with

all this. She was the responsible

one—the balancer of books. Family

economics were already strained, and

Dad's fine Chesterfield overcoat,

his suit coat, shirt, and tie were

ruined. Although Dad laughed about

this for the rest of his life, that

afternoon, as reality set in, it

wasn't quite so funny.

Why such zaniness? Why such

destruction? The "jazz disease," Dad

called it. A little madness seemed

to go with the territory. Obsessed

with jazz, on fire with youthful

exuberance, possessors of inborn

musical talent, they were at the

same time frustrated eccentrics who

tended to have disrespect for the

bandleaders who employed them. Of

course, they wanted perfection both

in music and in the music business,

and they rarely got it.

One night, after a commercial gig he

could barely tolerate, Bob McClendon

quit the business and drove to the

middle of the Trinity River Viaduct

where he contemptuously threw the

drums he loved to play into the

Trinity and watched them float away.

Two weeks later, desperate to play,

he bought a funny-looking old set

that had been gathering dust around

the Musician's Union. The Union

secretary had brought them back from

France at the end of World War I.

McClendon paid him $5.00 for them,

took them away and made music on

them. Like any addict, he didn't

seem to especially like music while

he was playing but he couldn't live

without it. The jazz disease, no

doubt.

Too much drinking fit right in with

all of this. In fact, drinking and

driving were standard for those guys

in those years. Behind the wheel,

they would often take a slug and

follow with a quick 7-Up chaser. As

a boy, I rode in the back seat and

was known to drink up the chaser

when nobody was looking.

One day I was rolling along in the

back seat of the "Bronze Beauty"

(cornetist Garner Clark's very used

Packard was painted bronze). Dad was

driving, Garner rode in the front

seat. As we passed through a Dallas

neighborhood, we went by a house

with a young boy seated on its front

porch, playing a trumpet. Garner

blanched and commanded, "Stop the

car!" We backed up, and gradually

the house and young aspiring

trumpeter came back into view.

Garner got out, stood on the running

board, and called over the top of

the Bronze Beauty to the boy, "Don't

do it! Give it up, before it's too

late!" In my father's life, this

wild, heavy-drinking, jazz-crazy

chase was coming to an end. Like any

strong beast, all this didn't die

easily but struggled on and off

until March, 1953, when Dad took his

last drink and, at least for a

while, put his horn away.

We moved to San Antonio on my 12th

birthday. What a drag, man! I didn't

want to move to San Antonio. Leave

my friends? (I was 12 years old,

remember!). Oh, what a terrible

drag!

But for my parents, San Antonio was

the "promised land." A second chance

at life. Dad, now sober, had a

wonderful business opportunity, and

he meant to make the best of it. He

threw himself in with his amazing

energy, drive, and determination as

he made up for lost time. He used

his father and older brother Marvin

as his models and worked hard and

smart, and as he zoomed along he

built a big new business. The jazz

that had driven so much of his life

was gone. To everyone's surprise, I

began to become obsessed with jazz

just as Dad was putting it down.

We lived for a while in a modest

rent house, and Dad's collection of

78 RPM records, complete in its own

large stand-up chest, was placed in

my bedroom as the house offered no

other practical place for them.

So there I was, blue and lonely, 12

years old, nothing to console me

except those old scratchy records.

Gradually, they started coming to my

aid.

The rest of the family was too busy

to notice, but I escaped into Louis

Armstrong records. Putting hard

mileage on the already worn 78s, I

memorized Louis' solos and riffs.

Louis to the rescue. Bob Crosby was

well-represented in the records as

was the great Benny Goodman.

Eventually, I discovered Bix.

My musical beginnings were certainly

not normal. I wasn't in the Junior

High Band and I didn't have a

musical instrument of any kind. But

I was submerged in this old jazz and

was easily memorizing the work of

the great masters. I'd go around all

day whistling constantly to myself.

Bix and his Gang were my companions.

"Thou Swell," "Jazz Me Blues," "Ol'

Man River," "Royal Garden Blues."

I'd whistle the entire record:

intros, ensembles, interludes, and

solos.

One day I was absent-mindedly doing

my whistling thing when my melody

(or I should say, Bix's melody)

caught my father's ear. "Hey!" he

said, not realizing the source of my

song, "That's pretty good! Maybe you

should take up some kind of horn."

That was all I needed. It was just a

casual remark, and Dad wouldn't have

dreamed he'd just helped set me on

the jazz road. Oh, I thought, what

an idea—a horn!

I started thinking that maybe I

should get a trombone. It looked

easy to me: for a lower note just

shove the slide out a little more.

But I never got a chance to find out

about the trombone the hard way, as

fate had placed an interesting

antique cornet in my path. There it

was in a pawn shop window. I had

arrived there strictly by chance,

and spotted it from a restaurant

across the street. It drew me over

like a magnet. I could have sooner

ignored the Great Wall of China had

it suddenly appeared across the

street.

After several negotiating sessions

with the pawn broker, I became the

proud owner of a C. Bruno and Sons

Bb cornet; approximate date of

issue: 1905, price: $7.00. I bought

a book, How to Play the Cornet, for

$1.00.

So I was off. In one day I mastered

the C scale, and on day two I was

able to sort of render the song

"Ja-Da." In about two more days I

had ready the chorus of "Tin Roof

Blues."

My father began to occasionally

retrieve his clarinet from its

almost-forgotten, lonely residence

in the back bedroom closet. It had

been patiently waiting there, behind

out-of-date double-breasted dinner

jackets and two-toned shoes, for its

comeback. With a new and different

kind of musical spark Dad gave

practical suggestions and

experimented with different

harmonies to my crude attempts at

melody.

After about a year of progress, and

while attending Alamo Heights High,

I formed a "kid's band." Dad would

occasionally join us, playing a

borrowed tenor saxophone as the

clarinet chair was taken. Unlikely

opportunities for employment began

to come our way. We played some

afternoons at the Alamo Heights

Dairy Queen in return for a credit

line against which burgers, milk

shakes, sundaes, and other goodies

would be drawn. A few times we

played at school, in the halls or

after lunch and for assemblies.

Eventually we played for a few

dances around town, some even at the

San Antonio Country Club. At one

point during these High School

years, I decided it would be good

for me to join the Alamo Heights

High School Band, and I called the

band director, Mr. Arsers.

Enthusiastically, I described my

progress, showed off my old,

funny-looking cornet, and explained

my interest in advancing my skills,

learning to read music, etc.

Oh, was I disappointed! Mr. Arsers

emphatically refused to let me join,

citing a number of objections,

mainly that I hadn't come up through

the school district's music program.

Undaunted, I waited two weeks and

approached him again, but was

rebuffed this time on grounds that

my old cornet was silver-plated. The

Alamo Heights Band contained only

brass lacquered instruments!

Thus rejected, I went on to my next

period class, choral singing (all

along I was a member of the high

school chorus) and the choral

director, Mr. Greenlee, noticed my

distress. I told my story about not

being accepted by the band. "Why do

you want to be in the band anyway?"

he asked. "I'll teach you and in

return you can be my errand boy."

So it went. I ran errands for Mr.

Greenlee and he taught me, mostly on

piano, about music theory—chords and

scales and a lot of very useful

stuff I would never have gotten in

the band.

Fats Waller's words ring true: "One

never knows, do one?"

Epilogue

During the 1940s, there were some 50 members of the proud Dallas jazz elite. Being of the next generation, I watched them gradually fall away. The last to go was the remarkable Bob McClendon, who was going strong well into his 80s. Handsome and dapper to the last, he continued to drum around town. All during the 1980s, Bob played twice-weekly at the Greenville Bar & Grill in Dallas and never failed to ignite the band and the crowd. Booze never did get to him like it did some of the othersI enjoyed seeing him a number of times during his last four years. He had become a mellow reflection of the wild man he once had been. But he still had that laugh and spirit and would get that twinkle in his eye when he talked of the old days...like the time he was with Clyde McCoy's band and the musicians and band bus were assembled early one morning on the sidewalk just outside a hotel where they had worked and slept the night before. McClendon didn't show up at the pre-arranged time to load his drums on top of the bus.

Clyde, impatient and pacing up and

down the sidewalk, sent a band

member up to McClendon's room on the

6th floor with instructions to get

the drums down there at once.

You can easily guess the outcome.

McClendon was still asleep and sent

word back to McCoy to relax or he'd

place the drums "where the sun don't

shine!" (He never could stand

McCoy's corny trumpet playing

anyway.) Of course, McCoy hit the

ceiling and sent his messenger back

with word to get those drums down

there immediately or McClendon was

fired. With that, McClendon, true to

form, opened the window and heaved

the drums out. As they crashed to

the sidewalk six floors below and

just down from where the band was

waiting, they broke all to pieces.

McCoy, the musicians, the bus

driver, and a few passersby stood

open-mouthed as McClendon, laughing,

went back to bed and at least for a

while entered the ranks of the

unemployed. Crazy? No, the jazz

disease!;